April 2018 is shaping up to be quite the month where art/sci events are concerned. I just published a March 27, 2018 posting titled ‘Curiosity collides with the quantum and with the Science Writers and Communicators of Canada in Vancouver (Canada)‘ and I’ve now received news about more happenings in Toronto and Ottawa. Plus, there’s a science-themed meeting organized by ARPICO (Society of Italian Researchers &; Professionals in Western Canada) featuring brains and brain imaging in Vancouver.

Toronto’s and Ottawa’s Emergence

There’s an art/sci exhibit opening, from a March 27, 2018 Art/Sci Salon announcement (received via email),

You are invited!FaceBook event:

The Oakwood Village Library and Arts Centre event:

341 Oakwood Avenue, Toronto, ON M6E 2W1

I check the library webpage listed in the above and found this artist’s statement,

Artist / Scientist Statement [Stephen Morris]

I am interested in self-organized, emergent patterns and textures. I make images of patterns both from the natural world and of experiments in my laboratory in the Department of Physics at the University of Toronto. Patterns naturally attract casual attention but are also the subject of serious scientific research. Some things just evolve all by themselves into strikingly regular shapes and textures. Why? These shapes emerge spontaneously from a dynamic process of growing, folding, cracking, wrinkling, branching, flowing and other kinds of morphological development. My photos are informed by the scientific aesthetic of nonlinear physics, and celebrate the subtle interplay of order and complexity in emergent patterns. They are a kind of “Scientific Folk Art” of the science of Emergence.

While the official opening is April 5, 2018, the event itself runs from April 1 – 30, 2018.

Next, there’s another March 27, 2018 announcement (received via email) from the Art/Sci Salon but this one concerns a series of talks about ’emergence’, Note: Some of the event information was a little difficult to decipher so I’ve added a note to the relevant section).

What is Emergent Form?

Nature teems with self-organized forms that seem to spring spontaneously from the smooth background of things, by mechanisms that are not always apparent. Think of rippled sand on a beach or regular stripes in the clouds. Plants, insects and animals exhibit spirals and spots and stripes in an exuberant riot of colours. Fluid flows in amazingly regular swirls and eddies. The emergence of form is ubiquitous, and presents a challenge and an inspiration to both artists and scientists. In mathematics, patterns appear as solutions of the nonlinear partial differential equations in the continuum limit of classical physics, chemistry and biology. In the arts and humanities, “emergent form” addresses the entangled ways in which humans, plants animals, microorganisms inevitably co-exist in the universe; the way that human intervention and natural transformation can generate new landscapes and new forms of life.

With Emergent Form, we want to question the idea of a fixed world.

For us, Emergent Form is not just a series of natural and human phenomena too complicated to understand, measure or predict, but also a concept to help us identify ways in which we can come to term with, and embrace their complexity as a source of inspiration.

Join us in Toronto and Ottawa for a series of interdisciplinary discussions, performances and exhibitions on Emergent Form on Apr 10, 11, 12 (Toronto) and Apr. 14 [2018] (Ottawa).

This series is the result of a collaboration among several parties. Each event of the series is different and has its dedicated RSVP

Tue. Apr 10 The Fields Institute, 222 College Street

Emergent form: an interdisciplinary concept 6:00-8:00 pm Pier Luigi Capucci, Accademia di Belle Arti Urbino. Founder and director, Noemalab*, Charles Sowers, Independent artist and exhibit designer, the Exploratorium, Stephen Morris, Professor of of Physics University of Toronto, Ron Wild, smART Maps

CLICK HERE FOR MORE AND TO RSVP

Wed. Apr 11 The Fields Institute6:00-8:00 pm

Anatomy of an Interconnected SystemA Performative Lecture with Margherita Pevere, Aalto University, Helsinki

CLICK HERE FOR MORE AND TO RSVP

Thu. Apr 12 (Note: I believe that from 5 – 6 pm, you’re invited to see Pevere’s exhibit and then proceed to Luella Massey Studio Theatre for performances)

5:00 pm Cabinets in the Koffler Student Centre [I believe this is at the University of Toronto] Anatomy of an Interconnected System An exhibition by Margherita Pevere

6:00 pm Luella Massey Studio Theatre, 4 Glen Morris Ave., Toronto biopoetriX – conFiGURing AI

6:00-8:00 pm Performance:

6:00pm Performance “Corpus Nil. A Ritual of Birth for a Modified Body” conceived and performed by Marco Donnarumma

6.30pm LAB dance: Blitz media posters on labs in the arts, sciences and engineering

7.10pm Panel: Performing AI, hybrid media and humans in/as technologyMarco Donnarumma, Doug van Nort (Dispersion Lab, York U.), Jane Tingley (Stratford User Research & Gameful Experiences Lab –SURGE-, U of Waterloo), Angela Schoellig (Dynamic Systems Lab, U of T)

Panel animators: Antje Budde (Digital Dramaturgy Lab) and Roberta Buiani (ArtSci Salon)

8.15pm Reception at the Italian Cultural Institute, 496 Huron St, Toronto

CLICK HERE FOR MORE AND TO RSVP

Ottawa. Sat. Apr. 14 National Arts Centre, 1 Elgin Street11:00 am-1:00 pm

Emergent Form and complex phenomenaA creative panel discussion and surprise demonstrationsWith Pier Luigi Capucci, Margherita Pevere, Marco Donnarumma, Stephen Morris

CLICK HERE FOR MORE AND TO RSVP

This event would not be possible without the support of The Fields Institute for Research in Mathematical Science, The Italian Embassy, the Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Toronto, the Digital Dramaturgy Lab, and the Istituto Italiano di Cultura. Many thanks to our community partner BYOR (Bring your own Robot)

I wonder if some of the funding from Italy is in support of Italian Research in World Day. This is the inaugural year for the event, which will be held annually on April 15.

Vancouver’s brains

The Society of Italian Researchers and Professionals in Western Canada (ARPICO) is hosting an event in Vancouver (from a March 22, 2018 ARICO announcement received via email),

Our second speaking event of the year, in collaboration with the Consulate General of Italy in Vancouver, has been scheduled for Wednesday, April 11th, 2018 at the Roundhouse Community Centre. Professor Vesna Sossi’s talk will be examining how positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has contributed to better understanding of the brain function and disease with particular focus on Parkinson’s disease. You can read a summary of Prof. Sossi’s lecture as well as her short professional biography at the bottom of this message.

This event is organized in collaboration with the Consulate General of Italy in Vancouver to celebrate the newly instituted Italian Research in the World Day, as part of the Piano Straordinario “Vivere all’Italiana” – Giornata della ricerca Italiana nel mondo. You can read more on our website event page.

We look forward to seeing everyone there.

Please register for the event by visiting the EventBrite link or RSVPing to info@arpico.ca.

The evening agenda is as follows:

- 6:45 pm – Doors Open

- 7:00 pm – Lecture by Prof. Vesna Sossi

- ~8:00 pm – Q & A Period

- Mingling & Refreshments until about 9:30 pm

If you have not yet RSVP’d, please do so on our EventBrite page.

Further details are also available at arpico.ca, our facebook page, and Eventbrite.

Imaging: A Window into the Brain

Brain illness, comprising neurological disorders, mental illness and addiction, is considered the major health challenge in the 21st century with a socio-economic cost greater than cancer and cardiovascular disease combined. There are at least three unique challenges hampering brain disease management: relative inaccessibility, disease onset often preceding the onset of clinical symptoms by many years and overlap between clinical and pathological symptoms that makes accurate disease identification often difficult. This talk will give examples of how positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has contributed to better understanding of the brain function and disease with particular focus on Parkinson’s disease. Emphasis will be placed on the interplay between scientific discoveries and instrumentation and data analysis development as exemplified by the current understanding of the brain function as comprised by interactions between connectivity networks and neurochemistry and advancement in multi-modal imaging such as simultaneous PET and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Vesna Sossi is a Professor in the University of British Columbia (UBC) Physics and Astronomy Department and at the UBC Djavad Mowafaghian Center for Brain Health. She directs the UBC Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging centre, which is known for its use of imaging as applied to neurodegeneration with emphasis on Parkinson’s disease. Her main areas of interest comprise development of imaging methods to enhance the investigation of neurochemical mechanisms that lead to an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD) and mechanisms that contribute to treatment-related complications. She uses PET imaging to explore how alterations of the different neurotransmitter systems contribute to different trajectories of disease progression. Her other areas of interest are PET image analysis, instrumentation and multi-modal, multi-parameter data analysis. She published more than 180 peer review papers, is funded by several granting agencies, including the Michael J Fox Foundation, and sits on several national and international review panels.

WHEN: Wednesday, April 11th, 2018 at 7:00pm (doors open at 6:45pm)

WHERE: Roundhouse Community Centre, Room B – 181 Roundhouse Mews, Vancouver, BC, V6Z 2W3

RSVP: Please RSVP at EventBrite (https://imaging-a-window-into-the-brain.eventbrite.ca) or email info@arpico.ca

Tickets are Needed

- Tickets are FREE, but all individuals are requested to obtain “free-admission” tickets on EventBrite site due to limited seating at the venue. Organizers need accurate registration numbers to manage wait lists and prepare name tags.

- All ARPICO events are 100% staffed by volunteer organizers and helpers, however, room rental, stationery, and guest refreshments are costs incurred and underwritten by members of ARPICO. Therefore to be fair, all audience participants are asked to donate to the best of their ability at the door or via EventBrite to “help” defray costs of the event.

You can find directions for the Roundhouse Community Centre here

I have one idle question. What’s going to happen these groups if Canadians change their use of Facebook or abandon the platform as they are threatening to do in the face of Cambridge Analytica’s use of their data? A March 25, 2018 article on huffingtonpost.ca outlines the latest about Canadians’ reaction to the Cambridge Analytical news according to an Angus Reid poll,

…

A survey by Angus Reid Institute suggests 73 per cent of Canadian Facebook users say they will make changes, while 27 per cent say it will be “business as usual.”

Nearly a quarter (23 per cent) said they would use Facebook less in the future, and 41 per cent of users said they would check and/or change their privacy settings.

The survey also found that one in 10 say they plan to abandon the platform, at least temporarily.

Facebook has been under fire for its ability to protect user privacy after Cambridge Analytica was accused of lifting the Facebook profiles of more than 50 million users without their permission.

There you have it.

*Well, a bit more information about one of the “Emergent’ speakers was received in an April 4, 2018 ArtSci Salon email announcement,

Do make sure to check out Pier Luigi Capucci’s EU-based (but with international breadth) Noemalab platform. https://noemalab.eu/ since the mid-nineties, this platform has been an important node of information for New Media Art and the relation between the arts and science.

noemalab’s blog regularly hosts reviews of events and conferences occurring around the world, including the Subtle Technologies Festival between 2007 and 2014. you can search its archives here http://blogs.noemalab.eu/

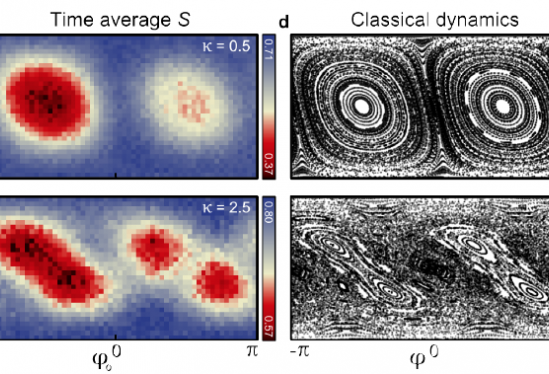

Capucci has been writing several reflections on emergent forms of Life and theorized what he called the “third life”. See a recent essay https://noemalab.eu/memo/events/evolutionary-creativity-the-inner-life-and-meaning-of-art/ here is a picture which I would love him to explain during Emergent Form. Intrigued? come listen to him!