After publishing a June 15, 2016 post about taking DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) beyond genetics, it seemed like a good to publish a companion piece featuring a more technical explanation of at least one way DNA might provide the base for living computers and robots. From a June 13, 2016 BrookHaven National Laboratory news release (also on EurekAlert),

A cube, an octahedron, a prism–these are among the polyhedral structures, or frames, made of DNA that scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have designed to connect nanoparticles into a variety of precisely structured three-dimensional (3D) lattices. The scientists also developed a method to integrate nanoparticles and DNA frames into interconnecting modules, expanding the diversity of possible structures.

These achievements, described in papers published in Nature Materials and Nature Chemistry, could enable the rational design of nanomaterials with enhanced or combined optical, electric, and magnetic properties to achieve desired functions.

“We are aiming to create self-assembled nanostructures from blueprints,” said physicist Oleg Gang, who led this research at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN), a DOE Office of Science User Facility at Brookhaven. “The structure of our nanoparticle assemblies is mostly controlled by the shape and binding properties of precisely designed DNA frames, not by the nanoparticles themselves. By enabling us to engineer different lattices and architectures without having to manipulate the particles, our method opens up great opportunities for designing nanomaterials with properties that can be enhanced by precisely organizing functional components. For example, we could create targeted light-absorbing materials that harness solar energy, or magnetic materials that increase information-storage capacity.”

The news release goes on to describe the frames,

Gang’s team has previously exploited DNA’s complementary base pairing–the highly specific binding of bases known by the letters A, T, G, and C that make up the rungs of the DNA double-helix “ladder”–to bring particles together in a precise way. Particles coated with single strands of DNA link to particles coated with complementary strands (A binds with T and G binds with C) while repelling particles coated with non-complementary strands.

They have also designed 3D DNA frames whose corners have single-stranded DNA tethers to which nanoparticles coated with complementary strands can bind. When the scientists mix these nanoparticles and frames, the components self-assemble into lattices that are mainly defined by the shape of the designed frame. The Nature Materials paper describes the most recent structures achieved using this strategy.

“In our approach, we use DNA frames to promote the directional interactions between nanoparticles such that the particles connect into specific configurations that achieve the desired 3D arrays,” said Ye Tian, lead author on the Nature Materials paper and a member of Gang’s research team. “The geometry of each particle-linking frame is directly related to the lattice type, though the exact nature of this relationship is still being explored.”

So far, the team has designed five polyhedral frame shapes–a cube, an octahedron, an elongated square bipyramid, a prism, and a triangular bypyramid–but a variety of other shapes could be created.

“The idea is to construct different 3D structures (buildings) from the same nanoparticle (brick),” said Gang. “Usually, the particles need to be modified to produce the desired structures. Our approach significantly reduces the structure’s dependence on the nature of the particle, which can be gold, silver, iron, or any other inorganic material.”

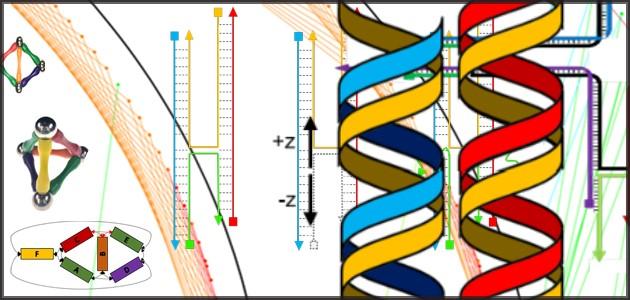

Nanoparticles (yellow balls) capped with short single-stranded DNA (blue squiggly lines) are mixed with polyhedral DNA frames (from top to bottom): cube, octahedron, elongated square bipyramid, prism, and triangular bipyramid. The frames’ vertices are encoded with complementary DNA strands for nanoparticle binding. When the corresponding frames and particles mix, they form a framework. Courtesy of Brookhaven National Laboratory

There’s also a discussion about how DNA origami was used to design the frames,

To design the frames, the team used DNA origami, a self-assembly technique in which short synthetic strands of DNA (staple strands) are mixed with a longer single strand of biologically derived DNA (scaffold strand). When the scientists heat and cool this mixture, the staple strands selectively bind with or “staple” the scaffold strand, causing the scaffold strand to repeatedly fold over onto itself. Computer software helps them determine the specific sequences for folding the DNA into desired shapes.

The folding of the single-stranded DNA scaffold introduces anchoring points that contain free “sticky” ends–unpaired strings of DNA bases–where nanoparticles coated with complementary single-strand tethers can attach. These sticky ends can be positioned anywhere on the DNA frame, but Gang’s team chose the corners so that multiple frames could be connected.

For each frame shape, the number of DNA strands linking a frame corner to an individual nanoparticle is equivalent to the number of edges converging at that corner. The cube and prism frames have three strands at each corner, for example. By making these corner tethers with varying numbers of bases, the scientists can tune the flexibility and length of the particle-frame linkages.

The interparticle distances are determined by the lengths of the frame edges, which are tens of nanometers in the frames designed to date, but the scientists say it should be possible to tailor the frames to achieve any desired dimensions.

The scientists verified the frame structures and nanoparticle arrangements through cryo-electron microscopy (a type of microscopy conducted at very low temperatures) at the CFN and Brookhaven’s Biology Department, and x-ray scattering at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), a DOE Office of Science User Facility at Brookhaven.

The team started with a relatively simple form (from the news release),

In the Nature Chemistry paper, Gang’s team described how they used a similar DNA-based approach to create programmable two-dimensional (2D), square-like DNA frames around single nanoparticles.

DNA strands inside the frames provide coupling to complementary DNA on the nanoparticles, essentially holding the particle inside the frame. Each exterior side of the frame can be individually encoded with different DNA sequences. These outer DNA strands guide frame-frame recognition and connection.

Gang likens these DNA-framed nanoparticle modules to Legos whose interactions are programmed: “Each module can hold a different kind of nanoparticle and interlock to other modules in different but specific ways, fully determined by the complementary pairing of the DNA bases on the sides of the frame.”

In other words, the frames not only determine if the nanoparticles will connect but also how they will connect. Programming the frame sides with specific DNA sequences means only frames with complementary sequences can link up.

Mixing different types of modules together can yield a variety of structures, similar to the constructs that can be generated from Lego pieces. By creating a library of the modules, the scientists hope to be able to assemble structures on demand.

Finally, the discussion turns to the assembly of multifuctional nanomaterials (from the news release),

The selectivity of the connections enables different types and sizes of nanoparticles to be combined into single structures.

The geometry of the connections, or how the particles are oriented in space, is very important to designing structures with desired functions. For example, optically active nanoparticles can be arranged in a particular geometry to rotate, filter, absorb, and emit light–capabilities that are relevant for energy-harvesting applications, such as display screens and solar panels.

By using different modules from the “library,” Gang’s team demonstrated the self-assembly of one-dimensional linear arrays, “zigzag” chains, square-shaped and cross-shaped clusters, and 2D square lattices. The scientists even generated a simplistic nanoscale model of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

“We wanted to demonstrate that complex nanoparticle architectures can be self-assembled using our approach,” said Gang.

Again, the scientists used sophisticated imaging techniques–electron and atomic force microscopy at the CFN and x-ray scattering at NSLS-II–to verify that their structures were consistent with the prescribed designs and to study the assembly process in detail.

“Although many additional studies are required, our results show that we are making advances toward our goal of creating designed matter via self-assembly, including periodic particle arrays and complex nanoarchitectures with freeform shapes,” said Gang. “Our approach is exciting because it is a new platform for nanoscale manufacturing, one that can lead to a variety of rationally designed functional materials.”

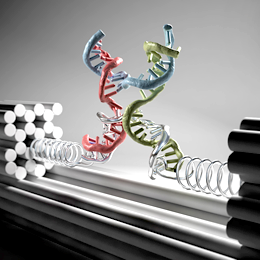

Here’s an image illustrating among other things da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man,

A schematic diagram (left) showing how a nanoparticle (yellow ball) is incorporated within a square-like DNA frame. The DNA strands inside the frame (blue squiggly lines) are complementary to the DNA strands on the nanoparticle; the colored strands on the outer edges of the frame have different DNA sequences that determine how the DNA-framed nanoparticle modules can connect. The architecture shown (middle) is a simplistic nanoscale representation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, assembled from several module types. The scientists used atomic force microscopy to generate the high-magnification image of this assembly (right). Courtesy Brookhaven National Laboratory

I enjoy the overviews provided by various writers and thinkers in the field but it’s details such as these that are often most compelling to me.