Launched on Thursday, July 13, 2023 during UNESCO’s (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) “Global dialogue on the ethics of neurotechnology,” is a report tying together the usual measures of national scientific supremacy (number of papers published and number of patents filed) with information on corporate investment in the field. Consequently, “Unveiling the Neurotechnology Landscape: Scientific Advancements, Innovations and Major Trends” by Daniel S. Hain, Roman Jurowetzki, Mariagrazia Squicciarini, and Lihui Xu provides better insight into the international neurotechnology scene than is sometimes found in these kinds of reports. By the way, the report is open access.

Here’s what I mean, from the report‘s short summary,

…

Since 2013, government investments in this field have exceeded $6 billion. Private investment has also seen significant growth, with annual funding experiencing a 22-fold increase from 2010 to 2020, reaching $7.3 billion and totaling $33.2 billion.

This investment has translated into a 35-fold growth in neuroscience publications between 2000-2021 and 20-fold growth in innovations between 2022-2020, as proxied by patents. However, not all are poised to benefit from such developments, as big divides emerge.

Over 80% of high-impact neuroscience publications are produced by only ten countries, while 70% of countries contributed fewer than 10 such papers over the period considered. Similarly, five countries only hold 87% of IP5 neurotech patents.

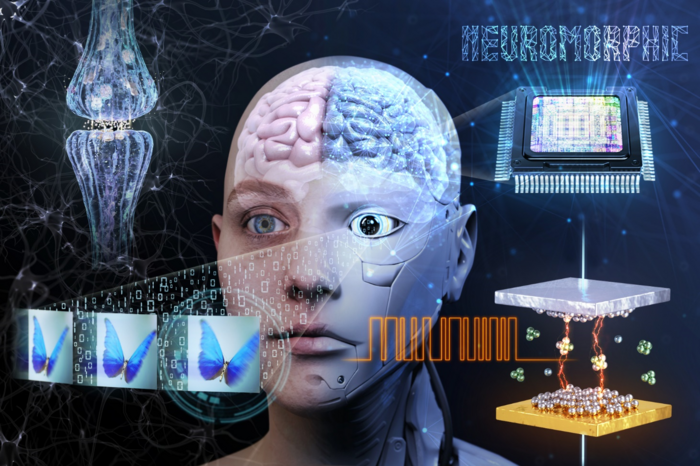

This report sheds light on the neurotechnology ecosystem, that is, what is being developed, where and by whom, and informs about how neurotechnology interacts with other technological trajectories, especially Artificial Intelligence [emphasis mine]. [p. 2]

…

The money aspect is eye-opening even when you already have your suspicions. Also, it’s not entirely unexpected to learn that only ten countries produce over 80% of the high impact neurotech papers and that only five countries hold 87% of the IP5 neurotech patents but it is stunning to see it in context. (If you’re not familiar with the term ‘IP5 patents’, scroll down in this post to the relevant subhead. Hint: It means the patent was filed in one of the top five jurisdictions; I’ll leave you to guess which ones those might be.)

“Since 2013 …” isn’t quite as informative as the authors may have hoped. I wish they had given a time frame for government investments similar to what they did for corporate investments (e.g., 2010 – 2020). Also, is the $6B (likely in USD) government investment cumulative or an estimated annual number? To sum up, I would have appreciated parallel structure and specificity.

Nitpicks aside, there’s some very good material intended for policy makers. On that note, some of the analysis is beyond me. I haven’t used anything even somewhat close to their analytical tools in years and years. This commentaries reflects my interests and a very rapid reading. One last thing, this is being written from a Canadian perspective. With those caveats in mind, here’s some of what I found.

A definition, social issues, country statistics, and more

There’s a definition for neurotechnology and a second mention of artificial intelligence being used in concert with neurotechnology. From the report‘s executive summary,

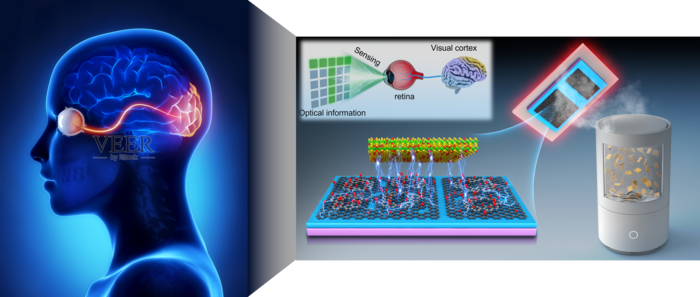

Neurotechnology consists of devices and procedures used to access, monitor, investigate, assess, manipulate, and/or emulate the structure and function of the neural systems of animals or human beings. It is poised to revolutionize our understanding of the brain and to unlock innovative solutions to treat a wide range of diseases and disorders.

…

Similarly to Artificial Intelligence (AI), and also due to its convergence with AI, neurotechnology may have profound societal and economic impact, beyond the medical realm. As neurotechnology directly relates to the brain, it triggers ethical considerations about fundamental aspects of human existence, including mental integrity, human dignity, personal identity, freedom of thought, autonomy, and privacy [emphases mine]. Its potential for enhancement purposes and its accessibility further amplifies its prospect social and societal implications.

…

The recent discussions held at UNESCO’s Executive Board further shows Member States’ desire to address the ethics and governance of neurotechnology through the elaboration of a new standard-setting instrument on the ethics of neurotechnology, to be adopted in 2025. To this end, it is important to explore the neurotechnology landscape, delineate its boundaries, key players, and trends, and shed light on neurotech’s scientific and technological developments. [p. 7]

…

Here’s how they sourced the data for the report,

The present report addresses such a need for evidence in support of policy making in

relation to neurotechnology by devising and implementing a novel methodology on data from scientific articles and patents:

● We detect topics over time and extract relevant keywords using a transformer-

based language models fine-tuned for scientific text. Publication data for the period

2000-2021 are sourced from the Scopus database and encompass journal articles

and conference proceedings in English. The 2,000 most cited publications per year

are further used in in-depth content analysis.

● Keywords are identified through Named Entity Recognition and used to generate

search queries for conducting a semantic search on patents’ titles and abstracts,

using another language model developed for patent text. This allows us to identify

patents associated with the identified neuroscience publications and their topics.

The patent data used in the present analysis are sourced from the European

Patent Office’s Worldwide Patent Statistical Database (PATSTAT). We consider

IP5 patents filed between 2000-2020 having an English language abstract and

exclude patents solely related to pharmaceuticals.

This approach allows mapping the advancements detailed in scientific literature to the technological applications contained in patent applications, allowing for an analysis of the linkages between science and technology. This almost fully automated novel approach allows repeating the analysis as neurotechnology evolves. [pp. 8-9[

Findings in bullet points,

Key stylized facts are:

● The field of neuroscience has witnessed a remarkable surge in the overall number

of publications since 2000, exhibiting a nearly 35-fold increase over the period

considered, reaching 1.2 million in 2021. The annual number of publications in

neuroscience has nearly tripled since 2000, exceeding 90,000 publications a year

in 2021. This increase became even more pronounced since 2019.

● The United States leads in terms of neuroscience publication output (40%),

followed by the United Kingdom (9%), Germany (7%), China (5%), Canada (4%),

Japan (4%), Italy (4%), France (4%), the Netherlands (3%), and Australia (3%).

These countries account for over 80% of neuroscience publications from 2000 to

2021.

● Big divides emerge, with 70% of countries in the world having less than 10 high-

impact neuroscience publications between 2000 to 2021.

● Specific neurotechnology-related research trends between 2000 and 2021 include:

○ An increase in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) research around 2010,

maintaining a consistent presence ever since.

○ A significant surge in Epilepsy Detection research in 2017 and 2018,

reflecting the increased use of AI and machine learning in healthcare.

○ Consistent interest in Neuroimaging Analysis, which peaks around 2004,

likely because of its importance in brain activity and language

comprehension studies.

○ While peaking in 2016 and 2017, Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) remains a

persistent area of research, underlining its potential in treating conditions

like Parkinson’s disease and essential tremor.

● Between 2000 and 2020, the total number of patent applications in this field

increased significantly, experiencing a 20-fold increase from less than 500 to over

12,000. In terms of annual figures, a consistent upward trend in neurotechnology-10

related patent applications emerges, with a notable doubling observed between

2015 and 2020.

• The United States account for nearly half of all worldwide patent applications (47%).

Other major contributors include South Korea (11%), China (10%), Japan (7%),

Germany (7%), and France (5%). These five countries together account for 87%

of IP5 neurotech patents applied between 2000 and 2020.

○ The United States has historically led the field, with a peak around 2010, a

decline towards 2015, and a recovery up to 2020.

○ South Korea emerged as a significant contributor after 1990, overtaking

Germany in the late 2000s to become the second-largest developer of

neurotechnology. By the late 2010s, South Korea’s annual neurotechnology

patent applications approximated those of the United States.

○ China exhibits a sharp increase in neurotechnology patent applications in

the mid-2010s, bringing it on par with the United States in terms of

application numbers.

● The United States ranks highest in both scientific publications and patents,

indicating their strong ability to transform knowledge into marketable inventions.

China, France, and Korea excel in leveraging knowledge to develop patented

innovations. Conversely, countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy,

Canada, Brazil, and Australia lag behind in effectively translating neurotech

knowledge into patentable innovations.

● In terms of patent quality measured by forward citations, the leading countries are

Germany, US, China, Japan, and Korea.

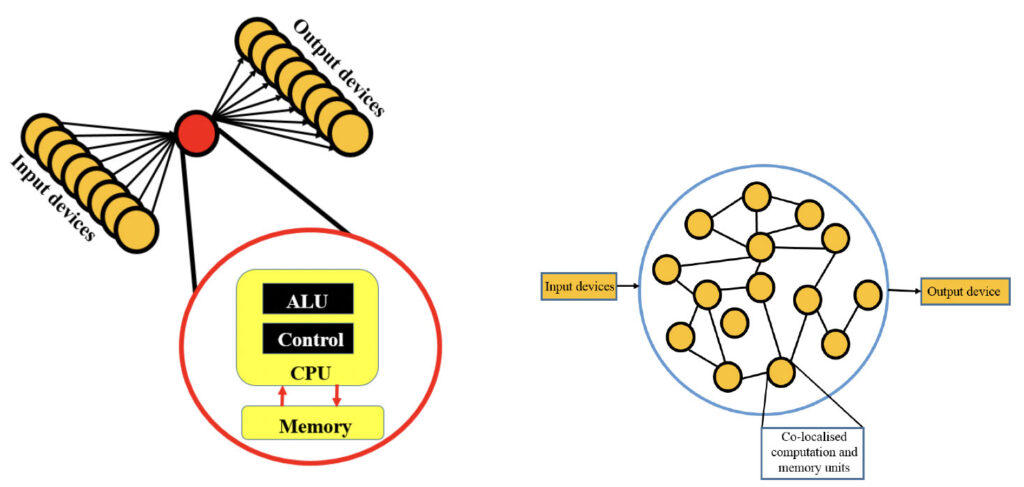

● A breakdown of patents by technology field reveals that Computer Technology is

the most important field in neurotechnology, exceeding Medical Technology,

Biotechnology, and Pharmaceuticals. The growing importance of algorithmic

applications, including neural computing techniques, also emerges by looking at

the increase in patent applications in these fields between 2015-2020. Compared

to the reference year, computer technologies-related patents in neurotech

increased by 355% and by 92% in medical technology.

● An analysis of the specialization patterns of the top-5 countries developing

neurotechnologies reveals that Germany has been specializing in chemistry-

related technology fields, whereas Asian countries, particularly South Korea and

China, focus on computer science and electrical engineering-related fields. The

United States exhibits a balanced configuration with specializations in both

chemistry and computer science-related fields.

● The entities – i.e. both companies and other institutions – leading worldwide

innovation in the neurotech space are: IBM (126 IP5 patents, US), Ping An

Technology (105 IP5 patents, CH), Fujitsu (78 IP5 patents, JP), Microsoft (76 IP511

patents, US)1, Samsung (72 IP5 patents, KR), Sony (69 IP5 patents JP) and Intel

(64 IP5 patents US)This report further proposes a pioneering taxonomy of neurotechnologies based on International Patent Classification (IPC) codes.

• 67 distinct patent clusters in neurotechnology are identified, which mirror the diverse research and development landscape of the field. The 20 most prominent neurotechnology groups, particularly in areas like multimodal neuromodulation, seizure prediction, neuromorphic computing [emphasis mine], and brain-computer interfaces, point to potential strategic areas for research and commercialization.

• The variety of patent clusters identified mirrors the breadth of neurotechnology’s potential applications, from medical imaging and limb rehabilitation to sleep optimization and assistive exoskeletons.

• The development of a baseline IPC-based taxonomy for neurotechnology offers a structured framework that enriches our understanding of this technological space, and can facilitate research, development and analysis. The identified key groups mirror the interdisciplinary nature of neurotechnology and underscores the potential impact of neurotechnology, not only in healthcare but also in areas like information technology and biomaterials, with non-negligible effects over societies and economies.1 If we consider Microsoft Technology Licensing LLM and Microsoft Corporation as being under the same umbrella, Microsoft leads worldwide developments with 127 IP5 patents. Similarly, if we were to consider that Siemens AG and Siemens Healthcare GmbH belong to the same conglomerate, Siemens would appear much higher in the ranking, in third position, with 84 IP5 patents. The distribution of intellectual property assets across companies belonging to the same conglomerate is frequent and mirrors strategic as well as operational needs and features, among others. [pp. 9-11]

Surprises and comments

Interesting and helpful to learn that “neurotechnology interacts with other technological trajectories, especially Artificial Intelligence;” this has changed and improved my understanding of neurotechnology.

It was unexpected to find Canada in the top ten countries producing neuroscience papers. However, finding out that the country lags in translating its ‘neuro’ knowledge into patentable innovation is not entirely a surprise.

It can’t be an accident that countries with major ‘electronics and computing’ companies lead in patents. These companies do have researchers but they also buy startups to acquire patents. They (and ‘patent trolls’) will also file patents preemptively. For the patent trolls, it’s a moneymaking proposition and for the large companies, it’s a way of protecting their own interests and/or (I imagine) forcing a sale.

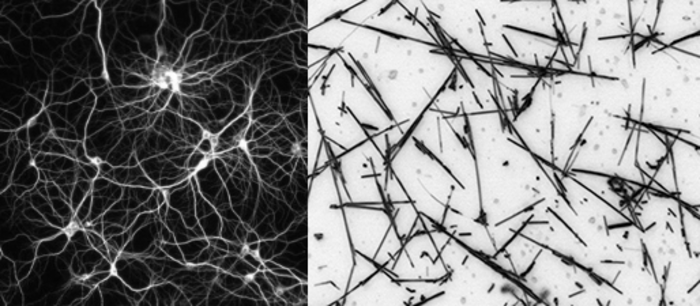

The mention of neuromorphic (brainlike) computing in the taxonomy section was surprising and puzzling. Up to this point, I’ve thought of neuromorphic computing as a kind of alternative or addition to standard computing but the authors have blurred the lines as per UNESCO’s definition of neurotechnology (specifically, “… emulate the structure and function of the neural systems of animals or human beings”) . Again, this report is broadening my understanding of neurotechnology. Of course, it required two instances before I quite grasped it, the definition and the taxonomy.

What’s puzzling is that neuromorphic engineering, a broader term that includes neuromorphic computing, isn’t used or mentioned. (For an explanation of the terms neuromorphic computing and neuromorphic engineering, there’s my June 23, 2023 posting, “Neuromorphic engineering: an overview.” )

The report

I won’t have time for everything. Here are some of the highlights from my admittedly personal perspective.

It’s not only about curing disease

From the report,

Neurotechnology’s applications however extend well beyond medicine [emphasis mine], and span from research, to education, to the workplace, and even people’s everyday life. Neurotechnology-based solutions may enhance learning and skill acquisition and boost focus through brain stimulation techniques. For instance, early research finds that brain- zapping caps appear to boost memory for at least one month (Berkeley, 2022). This could one day be used at home to enhance memory functions [emphasis mine]. They can further enable new ways to interact with the many digital devices we use in everyday life, transforming the way we work, live and interact. One example is the Sound Awareness wristband developed by a Stanford team (Neosensory, 2022) which enables individuals to “hear” by converting sound into tactile feedback, so that sound impaired individuals can perceive spoken words through their skin. Takagi and Nishimoto (2023) analyzed the brain scans taken through Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as individuals were shown thousands of images. They then trained a generative AI tool called Stable Diffusion2 on the brain scan data of the study’s participants, thus creating images that roughly corresponded to the real images shown. While this does not correspond to reading the mind of people, at least not yet, and some limitations of the study have been highlighted (Parshall, 2023), it nevertheless represents an important step towards developing the capability to interface human thoughts with computers [emphasis mine], via brain data interpretation.

While the above examples may sound somewhat like science fiction, the recent uptake of generative Artificial Intelligence applications and of large language models such as ChatGPT or Bard, demonstrates that the seemingly impossible can quickly become an everyday reality. At present, anyone can purchase online electroencephalogram (EEG) devices for a few hundred dollars [emphasis mine], to measure the electrical activity of their brain for meditation, gaming, or other purposes. [pp. 14-15]

This is very impressive achievement. Some of the research cited was published earlier this year (2023). The extraordinary speed is a testament to the efforts by the authors and their teams. It’s also a testament to how quickly the field is moving.

I’m glad to see the mention of and focus on consumer neurotechnology. (While the authors don’t speculate, I am free to do so.) Consumer neurotechnology could be viewed as one of the steps toward normalizing a cyborg future for all of us. Yes, we have books, television programmes, movies, and video games, which all normalize the idea but the people depicted have been severely injured and require the augmentation. With consumer neurotechnology, you have easily accessible devices being used to enhance people who aren’t injured, they just want to be ‘better’.

This phrase seemed particularly striking “… an important step towards developing the capability to interface human thoughts with computers” in light of some claims made by the Australian military in my June 13, 2023 posting “Mind-controlled robots based on graphene: an Australian research story.” (My posting has an embedded video demonstrating the Brain Robotic Interface (BRI) in action. Also, see the paragraph below the video for my ‘measured’ response.)

There’s no mention of the military in the report which seems more like a deliberate rather than inadvertent omission given the importance of military innovation where technology is concerned.

This section gives a good overview of government initiatives (in the report it’s followed by a table of the programmes),

Thanks to the promises it holds, neurotechnology has garnered significant attention from both governments and the private sector and is considered by many as an investment priority. According to the International Brain Initiative (IBI), brain research funding has become increasingly important over the past ten years, leading to a rise in large-scale state-led programs aimed at advancing brain intervention technologies(International Brain Initiative, 2021). Since 2013, initiatives such as the United States’ Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative and the European Union’s Human Brain Project (HBP), as well as major national initiatives in China, Japan and South Korea have been launched with significant funding support from the respective governments. The Canadian Brain Research Strategy, initially operated as a multi- stakeholder coalition on brain research, is also actively seeking funding support from the government to transform itself into a national research initiative (Canadian Brain Research Strategy, 2022). A similar proposal is also seen in the case of the Australian Brain Alliance, calling for the establishment of an Australian Brain Initiative (Australian Academy of Science, n.d.). [pp. 15-16]

Privacy

There are some concerns such as these,

Beyond the medical realm, research suggests that emotional responses of consumers

related to preferences and risks can be concurrently tracked by neurotechnology, such

as neuroimaging and that neural data can better predict market-level outcomes than

traditional behavioral data (Karmarkar and Yoon, 2016). As such, neural data is

increasingly sought after in the consumer market for purposes such as digital

phenotyping4, neurogaming 5,and neuromarketing6 (UNESCO, 2021). This surge in demand gives rise to risks like hacking, unauthorized data reuse, extraction of privacy-sensitive information, digital surveillance, criminal exploitation of data, and other forms of abuse. These risks prompt the question of whether neural data needs distinct definition and safeguarding measures.These issues are particularly relevant today as a wide range of electroencephalogram (EEG) headsets that can be used at home are now available in consumer markets for purposes that range from meditation assistance to controlling electronic devices through the mind. Imagine an individual is using one of these devices to play a neurofeedback game, which records the person’s brain waves during the game. Without the person being aware, the system can also identify the patterns associated with an undiagnosed mental health condition, such as anxiety. If the game company sells this data to third parties, e.g. health insurance providers, this may lead to an increase of insurance fees based on undisclosed information. This hypothetical situation would represent a clear violation of mental privacy and of unethical use of neural data.

Another example is in the field of advertising, where companies are increasingly interested in using neuroimaging to better understand consumers’ responses to their products or advertisements, a practice known as neuromarketing. For instance, a company might use neural data to determine which advertisements elicit the most positive emotional responses in consumers. While this can help companies improve their marketing strategies, it raises significant concerns about mental privacy. Questions arise in relation to consumers being aware or not that their neural data is being used, and in the extent to which this can lead to manipulative advertising practices that unfairly exploit unconscious preferences. Such potential abuses underscore the need for explicit consent and rigorous data protection measures in the use of neurotechnology for neuromarketing purposes. [pp. 21-22]

Legalities

Some countries already have laws and regulations regarding neurotechnology data,

At the national level, only a few countries have enacted laws and regulations to protect mental integrity or have included neuro-data in personal data protection laws (UNESCO, University of Milan-Bicocca (Italy) and State University of New York – Downstate Health Sciences University, 2023). Examples are the constitutional reform undertaken by Chile (Republic of Chile, 2021), the Charter for the responsible development of neurotechnologies of the Government of France (Government of France, 2022), and the Digital Rights Charter of the Government of Spain (Government of Spain, 2021). They propose different approaches to the regulation and protection of human rights in relation to neurotechnology. Countries such as the UK are also examining under which circumstances neural data may be considered as a special category of data under the general data protection framework (i.e. UK’s GDPR) (UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office, 2023) [p. 24]

As you can see, these are recent laws. There doesn’t seem to be any attempt here in Canada even though there is an act being reviewed in Parliament that could conceivably include neural data. This is from my May 1, 2023 posting,

Bill C-27 (Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2022) is what I believe is called an omnibus bill as it includes three different pieces of proposed legislation (the Consumer Privacy Protection Act [CPPA], the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act [AIDA], and the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act [PIDPTA]). [emphasis added July 11, 2023] You can read the Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) Canada summary here or a detailed series of descriptions of the act here on the ISED’s Canada’s Digital Charter webpage.

My focus at the time was artificial intelligence and, now, after reading this UNESCO report and briefly looking at the Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) Canada summary and a detailed series of descriptions of the act on ISED’s Canada’s Digital Charter webpage, I don’t see anything that specifies neural data but it’s not excluded either.

IP5 patents

Here’s the explanation (the footnote is included at the end of the excerpt),

IP5 patents represent a subset of overall patents filed worldwide, which have the

characteristic of having been filed in at least one top intellectual property offices (IPO)

worldwide (the so called IP5, namely the Chinese National Intellectual Property

Administration, CNIPA (formerly SIPO); the European Patent Office, EPO; the Japan

Patent Office, JPO; the Korean Intellectual Property Office, KIPO; and the United States

Patent and Trademark Office, USPTO) as well as another country, which may or may not be an IP5. This signals their potential applicability worldwide, as their inventiveness and industrial viability have been validated by at least two leading IPOs. This gives these patents a sort of “quality” check, also since patenting inventions is costly and if applicants try to protect the same invention in several parts of the world, this normally mirrors that the applicant has expectations about their importance and expected value. If we were to conduct the same analysis using information about individually considered patent applied worldwide, i.e. without filtering for quality nor considering patent families, we would risk conducting a biased analysis based on duplicated data. Also, as patentability standards vary across countries and IPOs, and what matters for patentability is the existence (or not) of prior art in the IPO considered, we would risk mixing real innovations with patents related to catching up phenomena in countries that are not at the forefront of the technology considered.9 The five IP offices (IP5) is a forum of the five largest intellectual property offices in the world that was set up to improve the efficiency of the examination process for patents worldwide. The IP5 Offices together handle about 80% of the world’s patent applications, and 95% of all work carried out under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), see http://www.fiveipoffices.org. (Dernis et al., 2015) [p. 31]

AI assistance on this report

As noted earlier I have next to no experience with the analytical tools having not attempted this kind of work in several years. Here’s an example of what they were doing,

We utilize a combination of text embeddings based on Bidirectional Encoder

Representations from Transformer (BERT), dimensionality reduction, and hierarchical

clustering inspired by the BERTopic methodology 12 to identify latent themes within

research literature. Latent themes or topics in the context of topic modeling represent

clusters of words that frequently appear together within a collection of documents (Blei, 2012). These groupings are not explicitly labeled but are inferred through computational analysis examining patterns in word usage. These themes are ‘hidden’ within the text, only to be revealed through this analysis. ……

We further utilize OpenAI’s GPT-4 model to enrich our understanding of topics’ keywords and to generate topic labels (OpenAI, 2023), thus supplementing expert review of the broad interdisciplinary corpus. Recently, GPT-4 has shown impressive results in medical contexts across various evaluations (Nori et al., 2023), making it a useful tool to enhance the information obtained from prior analysis stages, and to complement them. The automated process enhances the evaluation workflow, effectively emphasizing neuroscience themes pertinent to potential neurotechnology patents. Notwithstanding existing concerns about hallucinations (Lee, Bubeck and Petro, 2023) and errors in generative AI models, this methodology employs the GPT-4 model for summarization and interpretation tasks, which significantly mitigates the likelihood of hallucinations. Since the model is constrained to the context provided by the keyword collections, it limits the potential for fabricating information outside of the specified boundaries, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reliability of the output. [pp. 33-34]

I couldn’t resist adding the ChatGPT paragraph given all of the recent hoopla about it.

Multimodal neuromodulation and neuromorphic computing patents

I think this gives a pretty good indication of the activity on the patent front,

The largest, coherent topic, termed “multimodal neuromodulation,” comprises 535

patents detailing methodologies for deep or superficial brain stimulation designed to

address neurological and psychiatric ailments. These patented technologies interact with various points in neural circuits to induce either Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) or Long-Term Depression (LTD), offering treatment for conditions such as obsession, compulsion, anxiety, depression, Parkinson’s disease, and other movement disorders. The modalities encompass implanted deep-brain stimulators (DBS), Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), and transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS). Among the most representative documents for this cluster are patents with titles: Electrical stimulation of structures within the brain or Systems and methods for enhancing or optimizing neural stimulation therapy for treating symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and or other movement disorders. [p.65]

Given my longstanding interest in memristors, which (I believe) have to a large extent helped to stimulate research into neuromorphic computing, this had to be included. Then, there was the brain-computer interfaces cluster,

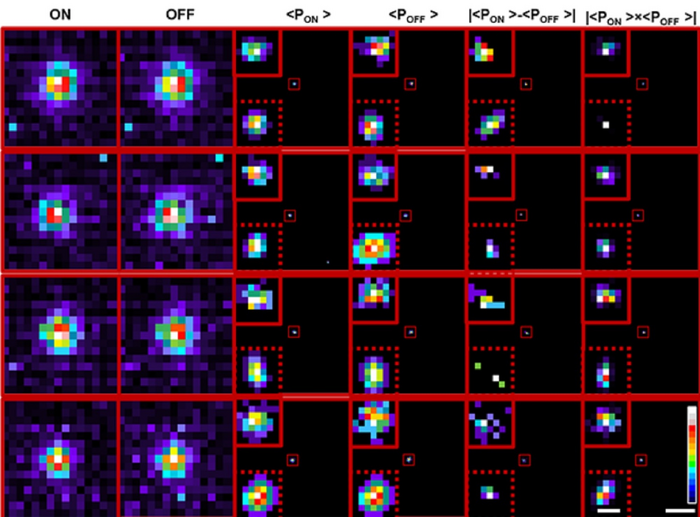

A cluster identified as “Neuromorphic Computing” consists of 366 patents primarily

focused on devices designed to mimic human neural networks for efficient and adaptable computation. The principal elements of these inventions are resistive memory cells and artificial synapses. They exhibit properties similar to the neurons and synapses in biological brains, thus granting these devices the ability to learn and modulate responses based on rewards, akin to the adaptive cognitive capabilities of the human brain.The primary technology classes associated with these patents fall under specific IPC

codes, representing the fields of neural network models, analog computers, and static

storage structures. Essentially, these classifications correspond to technologies that are key to the construction of computers and exhibit cognitive functions similar to human brain processes.Examples for this cluster include neuromorphic processing devices that leverage

variations in resistance to store and process information, artificial synapses exhibiting

spike-timing dependent plasticity, and systems that allow event-driven learning and

reward modulation within neuromorphic computers.In relation to neurotechnology as a whole, the “neuromorphic computing” cluster holds significant importance. It embodies the fusion of neuroscience and technology, thereby laying the basis for the development of adaptive and cognitive computational systems. Understanding this specific cluster provides a valuable insight into the progressing domain of neurotechnology, promising potential advancements across diverse fields, including artificial intelligence and healthcare.

The “Brain-Computer Interfaces” cluster, consisting of 146 patents, embodies a key aspect of neurotechnology that focuses on improving the interface between the brain and external devices. The technology classification codes associated with these patents primarily refer to methods or devices for treatment or protection of eyes and ears, devices for introducing media into, or onto, the body, and electric communication techniques, which are foundational elements of brain-computer interface (BCI) technologies.

Key patents within this cluster include a brain-computer interface apparatus adaptable to use environment and method of operating thereof, a double closed circuit brain-machine interface system, and an apparatus and method of brain-computer interface for device controlling based on brain signal. These inventions mainly revolve around the concept of using brain signals to control external devices, such as robotic arms, and improving the classification performance of these interfaces, even after long periods of non-use.

The inventions described in these patents improve the accuracy of device control, maintain performance over time, and accommodate multiple commands, thus significantly enhancing the functionality of BCIs.

Other identified technologies include systems for medical image analysis, limb rehabilitation, tinnitus treatment, sleep optimization, assistive exoskeletons, and advanced imaging techniques, among others. [pp. 66-67]

Having sections on neuromorphic computing and brain-computer interface patents in immediate proximity led to more speculation on my part. Imagine how much easier it would be to initiate a BCI connection if it’s powered with a neuromorphic (brainlike) computer/device. [ETA July 21, 2023: Following on from that thought, it might be more than just easier to initiate a BCI connection. Could a brainlike computer become part of your brain? Why not? it’s been successfully argued that a robotic wheelchair was part of someone’s body, see my January 30, 2013 posting and scroll down about 40% of the way.)]

Neurotech policy debates

The report concludes with this,

Neurotechnology is a complex and rapidly evolving technological paradigm whose

trajectories have the power to shape people’s identity, autonomy, privacy, sentiments,

behaviors and overall well-being, i.e. the very essence of what it means to be human.Designing and implementing careful and effective norms and regulations ensuring that neurotechnology is developed and deployed in an ethical manner, for the good of

individuals and for society as a whole, call for a careful identification and characterization of the issues at stake. This entails shedding light on the whole neurotechnology ecosystem, that is what is being developed, where and by whom, and also understanding how neurotechnology interacts with other developments and technological trajectories, especially AI. Failing to do so may result in ineffective (at best) or distorted policies and policy decisions, which may harm human rights and human dignity.…

Addressing the need for evidence in support of policy making, the present report offers first time robust data and analysis shedding light on the neurotechnology landscape worldwide. To this end, its proposes and implements an innovative approach that leverages artificial intelligence and deep learning on data from scientific publications and paten[t]s to identify scientific and technological developments in the neurotech space. The methodology proposed represents a scientific advance in itself, as it constitutes a quasi- automated replicable strategy for the detection and documentation of neurotechnology- related breakthroughs in science and innovation, to be repeated over time to account for the evolution of the sector. Leveraging this approach, the report further proposes an IPC-based taxonomy for neurotechnology which allows for a structured framework to the exploration of neurotechnology, to enable future research, development and analysis. The innovative methodology proposed is very flexible and can in fact be leveraged to investigate different emerging technologies, as they arise.

…

In terms of technological trajectories, we uncover a shift in the neurotechnology industry, with greater emphasis being put on computer and medical technologies in recent years, compared to traditionally dominant trajectories related to biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. This shift warrants close attention from policymakers, and calls for attention in relation to the latest (converging) developments in the field, especially AI and related methods and applications and neurotechnology.

This is all the more important and the observed growth and specialization patterns are unfolding in the context of regulatory environments that, generally, are either not existent or not fit for purpose. Given the sheer implications and impact of neurotechnology on the very essence of human beings, this lack of regulation poses key challenges related to the possible infringement of mental integrity, human dignity, personal identity, privacy, freedom of thought, and autonomy, among others. Furthermore, issues surrounding accessibility and the potential for neurotech enhancement applications triggers significant concerns, with far-reaching implications for individuals and societies. [pp. 72-73]

Last words about the report

Informative, readable, and thought-provoking. And, it helped broaden my understanding of neurotechnology.

Future endeavours?

I’m hopeful that one of these days one of these groups (UNESCO, Canadian Science Policy Centre, or ???) will tackle the issue of business bankruptcy in the neurotechnology sector. It has already occurred as noted in my ““Going blind when your neural implant company flirts with bankruptcy [long read]” April 5, 2022 posting. That story opens with a woman going blind in a New York subway when her neural implant fails. It’s how she found out the company, which supplied her implant was going out of business.

In my July 7, 2023 posting about the UNESCO July 2023 dialogue on neurotechnology, I’ve included information on Neuralink (one of Elon Musk’s companies) and its approval (despite some investigations) by the US Food and Drug Administration to start human clinical trials. Scroll down about 75% of the way to the “Food for thought” subhead where you will find stories about allegations made against Neuralink.

The end

If you want to know more about the field, the report offers a seven-page bibliography and there’s a lot of material here where you can start with this December 3, 2019 posting “Neural and technological inequalities” which features an article mentioning a discussion between two scientists. Surprisingly (to me), the source article is in Fast Company (a leading progressive business media brand), according to their tagline)..

I have two categories you may want to check: Human Enhancement and Neuromorphic Engineering. There are also a number of tags: neuromorphic computing, machine/flesh, brainlike computing, cyborgs, neural implants, neuroprosthetics, memristors, and more.

Should you have any observations or corrections, please feel free to leave them in the Comments section of this posting.