Where explosions are concerned you might expect to see some army research and you would be right. A June 29, 2020 news item on ScienceDaily breaks the news,

Since World War I, the vast majority of American combat casualties has come not from gunshot wounds but from explosions. Today, most soldiers wear a heavy, bullet-proof vest to protect their torso but much of their body remains exposed to the indiscriminate aim of explosive fragments and shrapnel.

Designing equipment to protect extremities against the extreme temperatures and deadly projectiles that accompany an explosion has been difficult because of a fundamental property of materials. Materials that are strong enough to protect against ballistic threats can’t protect against extreme temperatures and vice versa. As a result, much of today’s protective equipment is composed of multiple layers of different materials, leading to bulky, heavy gear that, if worn on the arms and legs, would severely limit a soldier’s mobility.

Now, Harvard University researchers, in collaboration with the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Soldier Center (CCDC SC) and West Point, have developed a lightweight, multifunctional nanofiber material that can protect wearers from both extreme temperatures and ballistic threats.

…

A June 29, 2020 Harvard University news release (also on EurekAlert) by Leah Burrows, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

“When I was in combat in Afghanistan, I saw firsthand how body armor could save lives,” said senior author Kit Parker, the Tarr Family Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and a lieutenant colonel in the United States Army Reserve. “I also saw how heavy body armor could limit mobility. As soldiers on the battlefield, the three primary tasks are to move, shoot, and communicate. If you limit one of those, you decrease survivability and you endanger mission success.”

“Our goal was to design a multifunctional material that could protect someone working in an extreme environment, such as an astronaut, firefighter or soldier, from the many different threats they face,” said Grant M. Gonzalez, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS and first author of the paper.

In order to achieve this practical goal, the researchers needed to explore the tradeoff between mechanical protection and thermal insulation, properties rooted in a material’s molecular structure and orientation.

Materials with strong mechanical protection, such as metals and ceramics, have a highly ordered and aligned molecular structure. This structure allows them to withstand and distribute the energy of a direct blow. Insulating materials, on the other hand, have a much less ordered structure, which prevents the transmission of heat through the material.

Kevlar and Twaron are commercial products used extensively in protective equipment and can provide either ballistic or thermal protection, depending on how they are manufactured. Woven Kevlar, for example, has a highly aligned crystalline structure and is used in protective bulletproof vests. Porous Kevlar aerogels, on the other hand, have been shown to have high thermal insulation.

“Our idea was to use this Kevlar polymer to combine the woven, ordered structure of fibers with the porosity of aerogels to make long, continuous fibers with porous spacing in between,” said Gonzalez. “In this system, the long fibers could resist a mechanical impact while the pores would limit heat diffusion.”

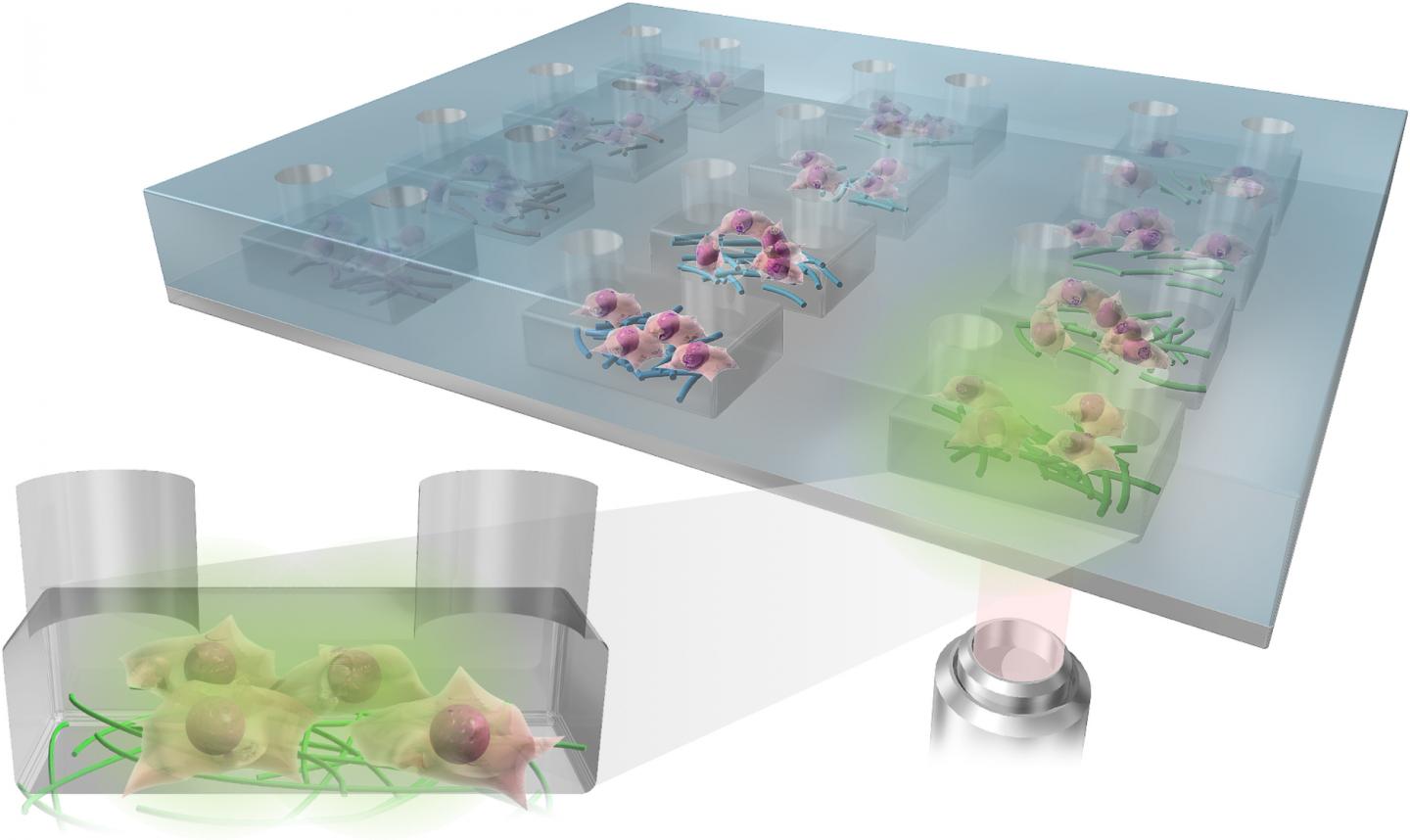

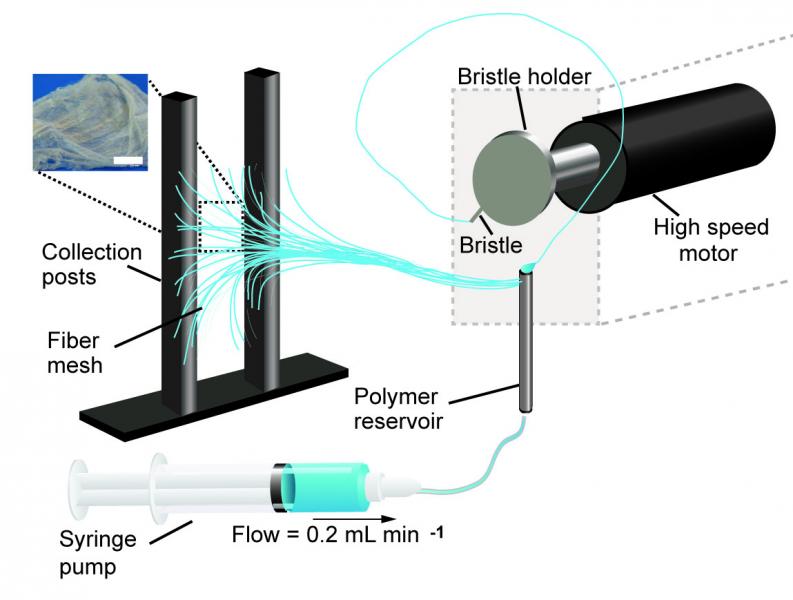

The research team used immersion Rotary Jet-Spinning (iRJS), a technique developed by Parker’s Disease Biophysics Group, to manufacture the fibers. In this technique, a liquid polymer solution is loaded into a reservoir and pushed out through a tiny opening by centrifugal force as the device spins. When the polymer solution shoots out of the reservoir, it first passes through an area of open air, where the polymers elongate and the chains align. Then the solution hits a liquid bath that removes the solvent and precipitates the polymers to form solid fibers. Since the bath is also spinning — like water in a salad spinner — the nanofibers follow the stream of the vortex and wrap around a rotating collector at the base of the device.

By tuning the viscosity of the liquid polymer solution, the researchers were able to spin long, aligned nanofibers into porous sheets — providing enough order to protect against projectiles but enough disorder to protect against heat. In about 10 minutes, the team could spin sheets about 10 by 30 centimeters in size.

To test the sheets, the Harvard team turned to their collaborators to perform ballistic tests. Researchers at CCDC SC in Natick, Massachusetts simulated shrapnel impact by shooting large, BB-like projectiles at the sample. The team performed tests by sandwiching the nanofiber sheets between sheets of woven Twaron. They observed little difference in protection between a stack of all woven Twaron sheets and a combined stack of woven Twaron and spun nanofibers.

“The capabilities of the CCDC SC allow us to quantify the successes of our fibers from the perspective of protective equipment for warfighters, specifically,” said Gonzalez.

“Academic collaborations, especially those with distinguished local universities such as Harvard, provide CCDC SC the opportunity to leverage cutting-edge expertise and facilities to augment our own R&D capabilities,” said Kathleen Swana, a researcher at CCDC SC and one of the paper’s authors. “CCDC SC, in return, provides valuable scientific and soldier-centric expertise and testing capabilities to help drive the research forward.”

In testing for thermal protection, the researchers found that the nanofibers provided 20 times the heat insulation capability of commercial Twaron and Kevlar.

“While there are improvements that could be made, we have pushed the boundaries of what’s possible and started moving the field towards this kind of multifunctional material,” said Gonzalez.

“We’ve shown that you can develop highly protective textiles for people that work in harm’s way,” said Parker. “Our challenge now is to evolve the scientific advances to innovative products for my brothers and sisters in arms.”

Harvard’s Office of Technology Development has filed a patent application for the technology and is actively seeking commercialization opportunities.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

para-Aramid Fiber Sheets for Simultaneous Mechanical and Thermal Protection in Extreme Environments by Grant M. Gonzalez, Janet Ward, John Song, Kathleen Swana, Stephen A. Fossey, Jesse L. Palmer, Felita W. Zhang, Veronica M. Lucian, Luca Cera, John F. Zimmerman, F. John Burpo, Kevin Kit Parker. Matter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matt.2020.06.001 Published:June 29, 2020

This paper is behind a paywall.

While this is the first time I’ve featured clothing/armour that’s protective against explosions I have on at least two occasions featured bulletproof clothing in a Canadian context. A November 4, 2013 posting had a story about a Toronto-based tailoring establishment, Garrison Bespoke, that was going to publicly test a bulletproof business suit. Should you be interested, it is possible to order the suit here. There’s also a February 11, 2020 posting announcing research into “Comfortable, bulletproof clothing for Canada’s Department of National Defence.”

![Figure 2: Brush-spinning of nanofibers. (Reprinted with permission by Wiley-VCH Verlag)) [downloaded from http://www.nanowerk.com/spotlight/spotid=41398.php]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Haribrush_nanofibres.jpg)

![[downloaded from http://www.chemistryviews.org/details/ezine/5712621/Musical_Molecules.html]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/MusicalMolecules-300x225.gif)