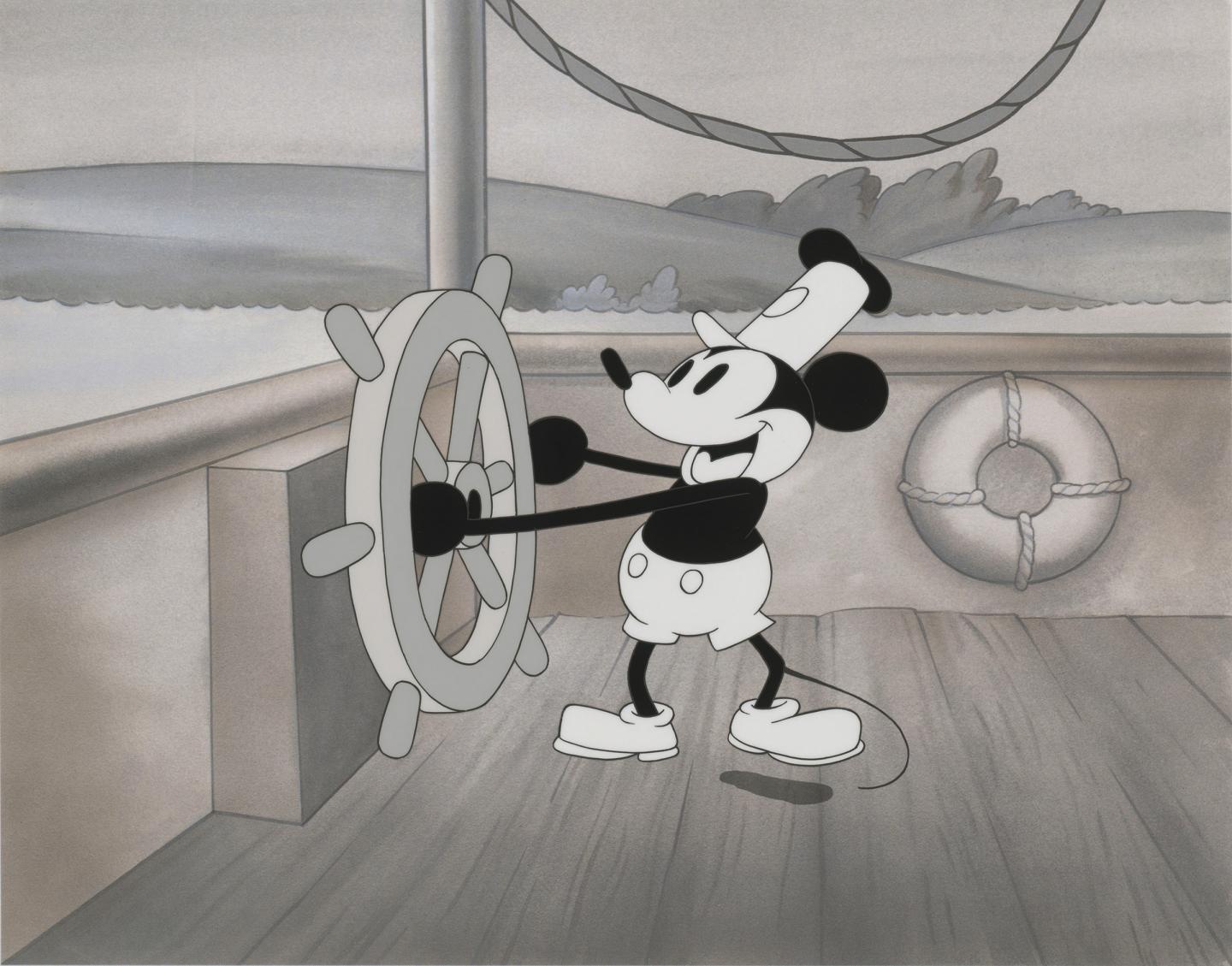

There’s an intriguing April 1, 2016 article by Josh Fischman for Scientific American about a problem with artworks from the 20th century and later—plastic-based materials (Note: A link has been removed),

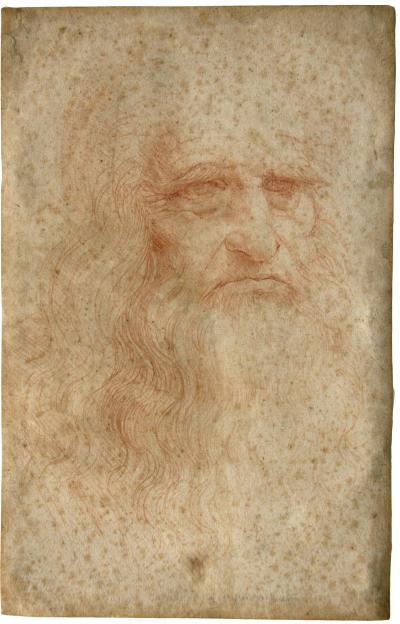

Conservators at museums and art galleries have a big worry. They believe there is a good chance the art they showcase now will not be fit to be seen in one hundred years, according to researchers in a project called Nanorestart. Why? After 1940, artists began using plastic-based material that was a far cry from the oil-based paints used by classical painters. Plastic is also far more fragile, it turns out. Its chemical bonds readily break. And they cannot be restored using techniques historically relied upon by conservators.

So art conservation scientists have turned to nanotechnology for help.

Sadly, there isn’t any detail in Fischman’s article (*ETA June 17, 2016 article [for Fast Company] by Charlie Sorrel, which features some good pictures, a succinct summary of Fischman’s article and a literary reference [Kurt Vonnegut’s Bluebeard]I*) about how nanotechnology is playing or might play a role in this conservation effort. Further investigation into the two projects (NanoRestART and POPART) mentioned by Fischman didn’t provide much more detail about NanoRestART’s science aspect but POPART does provide some details.

NanoRestART

It’s probably too soon (this project isn’t even a year-old) to be getting much in the way of the nanoscience details but NanoRestART has big plans according to its website homepage,

…

The conservation of this diverse cultural heritage requires advanced solutions at the cutting edge of modern chemistry and material science in an entirely new scientific framework that will be developed within NANORESTART project.

The NANORESTART project will focus on the synthesis of novel poly-functional nanomaterials and on the development of highly innovative restoration techniques to address the conservation of a wide variety of materials mainly used by modern and contemporary artists.

In NANORESTART, enterprises and academic centers of excellence in the field of synthesis and characterization of nano- and advanced materials have joined forces with complementary conservation institutions and freelance restorers. This multidisciplinary approach will cover the development of different materials in response to real conservation needs, the testing of such materials, the assessment of their environmental impact, and their industrial scalability.

NanoRestART’s (NANOmaterials for the REStoration of works of ART) project page spells out their goals in the order in which they are being approached,

…

The ground-breaking nature of our research can be more easily outlined by focussing on specific issues. The main conservation challenges that will be addressed in the project are:

Conservation challenge 1 – Cleaning of contemporary painted and plastic surfaces (CC1)

Conservation challenge 2 – Stabilization of canvases and painted layers in contemporary art (CC2)

Conservation challenge 3 – Removal of unwanted modern materials (CC3)

Conservation challenge 4 – Enhanced protection of artworks in museums and outdoors (CC4)

The European Commission provides more information about the project on its CORDIS website’s NanoRestART webpage including the start and end dates for the project and the consortium members,

From 2015-06-01 to 2018-12-01, ongoing project

CHALMERS TEKNISKA HOEGSKOLA AB

Sweden

MIRABILE ANTONIO

France

NATIONALMUSEET

Denmark

CONSIGLIO NAZIONALE DELLE RICERCHE

Italy

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK, NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND, CORK

Ireland

MBN NANOMATERIALIA SPA

Italy

KEMIJSKI INSTITUT

Slovenia

CHEVALIER AURELIA

France

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL

Brazil

UNIVERSITA CA’ FOSCARI VENEZIA

Italy

AKZO NOBEL PULP AND PERFORMANCE CHEMICALS AB

Sweden

COMMISSARIAT A L ENERGIE ATOMIQUE ET AUX ENERGIES ALTERNATIVES

France

ARKEMA FRANCE SA

France

UNIVERSIDAD DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA

Spain

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

United Kingdom

ZFB ZENTRUM FUR BUCHERHALTUNG GMBH

Germany

UNIVERSITAT DE BARCELONA

Spain

THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE TATE GALLERY

United Kingdom

ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA PER LA RICERCA INDUSTRIALE – AIRI

Italy

THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO

United States

MINISTERIO DE EDUCACION, CULTURA Y DEPORTE

Spain

STICHTING HET RIJKSMUSEUM

Netherlands

UNIVERSITEIT VAN AMSTERDAM

Netherlands

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO

Brazil

ACCADEMIA DI BELLE ARTI DI BRERA

Italy

It was a bit surprising to see Brazil and the US as participants but The Art Institute of Chicago has done nanotechnology-enabled conservation in the past as per my March 24, 2014 posting about a Renoir painting. I’m not familiar with the Brazilian organization.

POPART

POPART (Preservation of Plastic Artefacts in museum collections) mentioned by Fischman was a European Commission project which ran from 2008 – 2012. Reports can be found on the CORDIS Popart webpage. The final report has some interesting bits (Note: I have added subheads in the [] square brackets),

To achieve a valid comparison of the various invasive and non-invasive techniques proposed for the identification and characterisation of plastics, a sample collection (SamCo) of plastics artefacts of about 100 standard and reference plastic objects was gathered. SamCo was made up of two kinds of reference materials: standards and objects. Each standard represents the reference material of a pure plastic; while each object represents the reference of the same plastic as in the standards, but compounded with pigments, dyestuffs, fillers, anti oxidants, plasticizers etc. Three partners ICN [Instituut Collectie Nederland], V&A [Victoria and Albert Museum] and Natmus [National Museet] collected different natural and synthetic plastics from the ICN reference collections of plastic objects, from flea markets, antique shops and from private collections and from their own collection to contribute to SamCo, the sample collection for identification by POPART partners. …

…

As a successive step, the collections of the following museums were surveyed:

-Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A), London, U.K.

-Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

-Musée dArt Moderne et dArt Contemporaine (MAMAC) Nice, France

-Musée dArt moderne, St. Etienne, France

-Musée Galliera, Paris, France

At the V&A approximately 200 objects were surveyed. Good or fair conservation conditions were found for about 85% of the objects, whereas the remaining 15% was in poor or even in unacceptable (3%) conditions. In particular, crazing and delamination of polyurethane faux leather and surface stickiness and darkening of plasticized PVC were observed. The situation at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam was particularly favourable because a previous survey had been done in 1995 so that it was possible to make a comparison with the Popart survey in 2010. A total number of 40 objects, which comprised plastics early dating from the 1930s until the newer plastics from the 1980s, were considered and their actual conservation state compared with the 1995 records. Of the objects surveyed in 2010, it can be concluded that 21 remained in the same condition. 13 objects containing PA, PUR, PVC, PP or natural rubber changed due to chemical and physical degradation while works of art containing either PMMA or PS changed due to mechanical damages and incorrect artists technique (inappropriate adhesive) into a lesser condition. 6 works of art (containing either PA or PMMA or both) changed into a better condition due to restoration or replacements. More than 230 objects have been examined in the 3 museums in France. A particular effort was devoted to the identification of the constituting plastics materials. Surveys have been undertaken without any sophisticated equipment, in order to work in museums everyday conditions. Plastics hidden by other materials or by paint layers were not or hardly accessible, it is why the final count of some plastics may be under estimated in the final results. Another outcome is that plastic identification has been made at a general level only, by trying to identify the polymer family each plastic belongs to. Lastly, evidence of chemical degradation processes that do not cause visible or perceptible damage have not been detected and could not be taken in account in the final results.

… The most damaged artefacts resulted constituted by cellulose acetate, cellulose nitrate and PVC.

[Polly (the doll)]

One of the main issues that is of interest for conservators and curators is to assess which kinds of plastics are most vulnerable to deterioration and to what extent they can deteriorate under the environmental conditions normally encountered in museums. Although one might expect that real time deterioration could be ascertained by a careful investigation of museum objects on display or in storage, real objects or artworks may not sampled due to ethical considerations. Therefore, reference objects were prepared by Natmus in the form of a doll (Polly) for simultaneous exposures in different environmental conditions. The doll comprised of 11 different plastics representative of types typically found in modern museum collections. The 16 identical dolls realized were exposed in different places, not only in normal exhibit conditions, but also in some selected extreme conditions to ascertain possible acceleration of the deterioration process. In most cases the environmental parameters were also measured. The dolls were periodically evaluated by visual inspection and in selected cases by instrumental analyses.

…

In conclusion the experimental campaign carried out with Polly dolls can be viewed as a pilot study aimed at tackling the practical issues related to the monitoring of real three dimensional plastic artworks and the surrounding environment.

The overall exposure period (one year and half) was sufficient to observe initial changes in the more susceptible polymers, such as polyurethane ethers and esters, and polyamide, with detectable chromatic changes and surface effects. Conversely the other polymers were shown to be stable in the same conditions over this time period.

…

[Polly as an awareness raising tool]

Last but not least, the educational and communication benefits of an object like Polly facilitated the dissemination of the Popart Project to the public, and increased the awareness of issues associated with plastics in museum collections.

…

[Cleaning issues]

Mechanical cleaning has long been perceived as the least damaging technique to remove soiling from plastics. The results obtained from POPART suggest that the risks of introducing scratches or residues by mechanical cleaning are measurable. Some plastics were clearly more sensitive to mechanical damage than others. From the model plastics evaluated, HIPS was the most sensitive followed by HDPE, PVC, PMMA and CA. Scratches could not be measured on XPS due to its inhomogeneous surfaces. Plasticised PVC scratched easily, but appeared to repair itself because plasticiser migrated to surfaces and filled scratches.

Photo micrographs revealed that although all 22 cleaning materials evaluated in POPART scratched test plastics, some scratches were sufficiently shallow to be invisible to the naked eye. Duzzit and Scotch Brite sponges as well as all paper based products caused more scratching of surfaces than brushes and cloths. Some cleaning materials, notably Akapad yellow and white sponges, compressed air, latex and synthetic rubber sponges and goat hair brushes left residues on surfaces. These residues were only visible on glass-clear, transparent test plastics such as PMMA. HDPE and HIPS surfaces both had matte and roughened appearances after cleaning with dry-ice. XPS was completely destroyed by the treatment. No visible changes were present on PMMA and PVC.

Of the cleaning methods evaluated, only canned air, natural and synthetic feather duster left surfaces unchanged. Natural and synthetic feather duster, microfiber-, spectacle – and cotton cloths, cotton bud, sable hair brush and leather chamois showed good results when applied to clean model plastics.

Most mechanical cleaning materials induced static electricity after cleaning, causing immediate attraction of dust. It was also noticed that generally when adding an aqueous cleaning agent to a cleaning material, the area scratched was reduced. This implied that cleaning agents also functioned as lubricants. A similar effect was exhibited by white spirit and isopropanol.

Based on cleaning vectors, Judith Hofenk de Graaff detergent, distilled water and Dehypon LS45 were the least damaging cleaning agents for all model plastics evaluated. None of the aqueous cleaning agents caused visible changes when used in combination with the least damaging cleaning materials. Sable hair brush, synthetic feather duster and yellow Akapad sponge were unsuitable for applying aqueous cleaning agents. Polyvinyl acetate sponge swelled in contact with solvents and was only suitable for aqueous cleaning processes.

Based on cleaning vectors, white spirit was the least damaging solvent. Acetone and Surfynol 61 were the most damaging for all model plastics and cannot be recommended for cleaning plastics. Surfynol 61 dissolved polyvinyl acetate sponge and left a milky residue on surfaces, which was particularly apparent on clear PMMA surfaces. Surfynol 61 left residues on surfaces on evaporating and acetone evaporated too rapidly to lubricate cleaning materials thereby increasing scratching of surfaces.

Supercritical carbon dioxide induced discolouration and mechanical damage to the model plastics, particularly to XPS, CA and PMMA and should not be used for conservation cleaning of plastics.

…

Potential Impact:

Cultural heritage is recognised as an economical factor, the cost of decay of cultural heritage and the risk associated to some material in collection may be high. It is generally estimated that plastics, developed at great numbers since the 20th centurys interbellum, will not survive that long. This means that fewer generations will have access to lasting plastic art for study, contemplation and enjoyment. On the other hand will it normally be easier to reveal a contemporary objects technological secrets because of better documentation and easier access to artists working methods, ideas and intentions. A first more or less world encompassing recognition of the problems involved with museum objects made wholly or in part of plastics was through the conference Saving the twentieth century held in Ottawa, Canada in 1991. This was followed later by Modern Art, who cares in Amsterdam, The Netherlands in 1997, Mortality Immortality? The Legacy of Modern Art in Los Angeles, USA in 1998 and, for example much more recent, Plastics Looking at the future and learning from the Past in London, UK in 2007. A growing professional interest in the care of plastics was clearly reflected in the creation of an ICOM-CC working group dedicated to modern materials in 1996, its name change to Modern Materials and Contemporary Art in 2002, and its growing membership from 60 at inception to over 200 at the 16th triennial conference in Lisbon, Portugal in 2011 and tentatively to over 300 as one of the aims put forward in the 2011-2014 programme of that ICOM-CC working group. …

[Intellectual property]

Another element pertaining to conservation of modern art is the copyright of artists that extends at least 50 years beyond their death. Both, damage, value and copyright may influence the way by which damage is measured through scientific analysis, more specifically through the application of invasive or non invasive techniques. Any selection of those will not only have an influence on the extent of observable damage, but also on the detail of information gathered and necessary to explain damage and to suggest conservation measures.

[How much is deteriorating?]

… it is obvious from surveys carried out in several museums in France, the UK and The Netherlands that from 15 to 35 % of what I would then call an average plastic material based collection is in a poor to unacceptable condition. However, some 75 % would require cleaning,

I hope to find out more about how nanotechnology is expected to be implemented in the conservation and preservation of plastic-based art. The NanoRestART project started in June 2015 and hopefully more information will be disseminated in the next year or so.

While it’s not directly related, there was some work with conservation of daguerreotypes (19th century photographic technique) and nanotechnology mentioned in my Nov. 17, 2015 posting which was a followup to my Jan. 10, 2015 posting about the project and the crisis precipitating it.

*ETA June 30, 2016: Here’s clip from a BBC programme, Science in Action broadcast on June 30, 2016 featuring a chat with some of the scientists involved in the NanoRestArt project (Note: This excerpt is from a longer programme and seemingly starts in the middle of a conversation,)