The combination of the US Army, bacterial cellulose, and kombucha seems a little unusual. However, this January 26, 2021 U.S. Army Research Laboratory news release (also on EurekAlert) provides some clues as to how this combination makes sense,

Kombucha tea, a trendy fermented beverage, inspired researchers to develop a new way to generate tough, functional materials using a mixture of bacteria and yeast similar to the kombucha mother used to ferment tea.

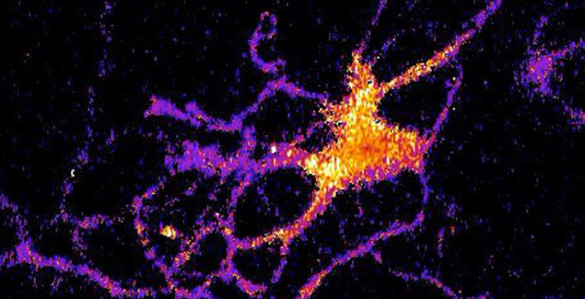

With Army funding, using this mixture, also called a SCOBY, or symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast, engineers at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] and Imperial College London produced cellulose embedded with enzymes that can perform a variety of functions, such as sensing environmental pollutants and self-healing materials.

The team also showed that they could incorporate yeast directly into the cellulose, creating living materials that could be used to purify water for Soldiers in the field or make smart packaging materials that can detect damage.

“This work provides insights into how synthetic biology approaches can harness the design of biotic-abiotic interfaces with biological organization over multiple length scales,” said Dr. Dawanne Poree, program manager, Army Research Office, an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, now known as DEVCOM, Army Research Laboratory. “This is important to the Army as this can lead to new materials with potential applications in microbial fuel cells, sense and respond systems, and self-reporting and self-repairing materials.”

The research, published in Nature Materials was funded by ARO [Army Research Office] and the Army’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies [ISN] at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The U.S. Army established the ISN in 2002 as an interdisciplinary research center devoted to dramatically improving the protection, survivability, and mission capabilities of the Soldier and Soldier-supporting platforms and systems.

“We foresee a future where diverse materials could be grown at home or in local production facilities, using biology rather than resource-intensive centralized manufacturing,” said Timothy Lu, an MIT associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science and of biological engineering.

Researchers produced cellulose embedded with enzymes, creating living materials that could be used to purify water for Soldiers in the field or make smart packaging materials that can detect damage. These fermentation factories, which usually contain one species of bacteria and one or more yeast species, produce ethanol, cellulose, and acetic acid that gives kombucha tea its distinctive flavor.

Most of the wild yeast strains used for fermentation are difficult to genetically modify, so the researchers replaced them with a strain of laboratory yeast called Saccharomyces cerevisiae. They combined the yeast with a type of bacteria called Komagataeibacter rhaeticus that their collaborators at Imperial College London had previously isolated from a kombucha mother. This species can produce large quantities of cellulose.

Because the researchers used a laboratory strain of yeast, they could engineer the cells to do any of the things that lab yeast can do, such as producing enzymes that glow in the dark, or sensing pollutants or pathogens in the environment. The yeast can also be programmed so that they can break down pollutants/pathogens after detecting them, which is highly relevant to Army for chem/bio defense applications.

“Our community believes that living materials could provide the most effective sensing of chem/bio warfare agents, especially those of unknown genetics and chemistry,” said Dr. Jim Burgess ISN program manager for ARO.

The bacteria in the culture produced large-scale quantities of tough cellulose that served as a scaffold. The researchers designed their system so that they can control whether the yeast themselves, or just the enzymes that they produce, are incorporated into the cellulose structure. It takes only a few days to grow the material, and if left long enough, it can thicken to occupy a space as large as a bathtub.

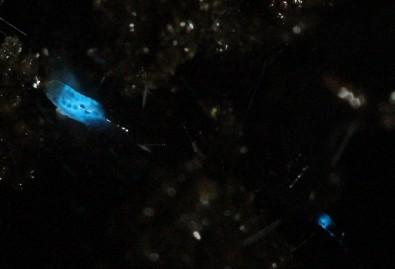

“We think this is a good system that is very cheap and very easy to make in very large quantities,” said MIT graduate student and the paper’s lead author, Tzu-Chieh Tang. To demonstrate the potential of their microbe culture, which they call Syn-SCOBY, the researchers created a material incorporating yeast that senses estradiol, which is sometimes found as an environmental pollutant. In another version, they used a strain of yeast that produces a glowing protein called luciferase when exposed to blue light. These yeasts could be swapped out for other strains that detect other pollutants, metals, or pathogens.

The researchers are now looking into using the Syn-SCOBY system for biomedical or food applications. For example, engineering the yeast cells to produce antimicrobials or proteins that could benefit human health.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Living materials with programmable functionalities grown from engineered microbial co-cultures by Charlie Gilbert, Tzu-Chieh Tang, Wolfgang Ott, Brandon A. Dorr, William M. Shaw, George L. Sun, Timothy K. Lu & Tom Ellis. Nature Materials (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-00857-5 Published: 11 January 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.