I was not expecting a Canadian connection but it seems we are heavily invested in this research at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), from a March 19, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily,

The researchers observed in an HOIP a “richness” of semiconducting physics created by what could be described as electrons dancing on chemical underpinnings that wobble like a funhouse floor in an earthquake. That bucks conventional wisdom because established semiconductors rely upon rigidly stable chemical foundations, that is to say, quieter molecular frameworks, to produce the desired quantum properties.

“We don’t know yet how it works to have these stable quantum properties in this intense molecular motion,” said first author Felix Thouin, a graduate research assistant at Georgia Tech. “It defies physics models we have to try to explain it. It’s like we need some new physics.”

Quantum properties surprise

Their gyrating jumbles have made HOIPs challenging to examine, but the team of researchers from a total of five research institutes in four countries succeeded in measuring a prototypical HOIP and found its quantum properties on par with those of established, molecularly rigid semiconductors, many of which are graphene-based.

“The properties were at least as good as in those materials and may be even better,” said Carlos Silva, a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemistry and Biochemistry. Not all semiconductors also absorb and emit light well, but HOIPs do, making them optoelectronic and thus potentially useful in lasers, LEDs, other lighting applications, and also in photovoltaics.

The lack of molecular-level rigidity in HOIPs also plays into them being more flexibly produced and applied.

Silva co-led the study with physicist Ajay Ram Srimath Kandada. Their team published the results of their study on two-dimensional HOIPs on March 8, 2018, in the journal Physical Review Materials. Their research was funded by EU Horizon 2020, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Fond Québécois pour la Recherche, the [National] Research Council of Canada, and the National Research Foundation of Singapore. [emphases mine]

The ‘solution solution’

Commonly, semiconducting properties arise from static crystalline lattices of neatly interconnected atoms. In silicon, for example, which is used in most commercial solar cells, they are interconnected silicon atoms. The same principle applies to graphene-like semiconductors.

“These lattices are structurally not very complex,” Silva said. “They’re only one atom thin, and they have strict two-dimensional properties, so they’re much more rigid.”

“You forcefully limit these systems to two dimensions,” said Srimath Kandada, who is a Marie Curie International Fellow at Georgia Tech and the Italian Institute of Technology. “The atoms are arranged in infinitely expansive, flat sheets, and then these very interesting and desirable optoelectronic properties emerge.”

These proven materials impress. So, why pursue HOIPs, except to explore their baffling physics? Because they may be more practical in important ways.

“One of the compelling advantages is that they’re all made using low-temperature processing from solutions,” Silva said. “It takes much less energy to make them.”

By contrast, graphene-based materials are produced at high temperatures in small amounts that can be tedious to work with. “With this stuff (HOIPs), you can make big batches in solution and coat a whole window with it if you want to,” Silva said.

Funhouse in an earthquake

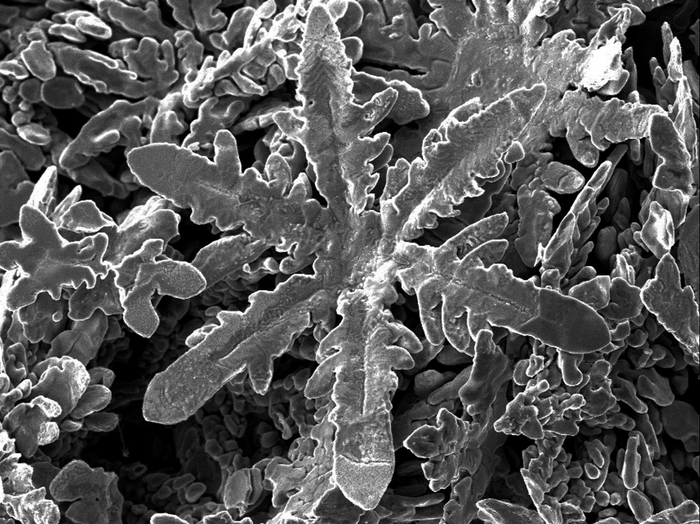

For all an HOIP’s wobbling, it’s also a very ordered lattice with its own kind of rigidity, though less limiting than in the customary two-dimensional materials.

“It’s not just a single layer,” Srimath Kandada said. “There is a very specific perovskite-like geometry.” Perovskite refers to the shape of an HOIPs crystal lattice, which is a layered scaffolding.

“The lattice self-assembles,” Srimath Kandada said, “and it does so in a three-dimensional stack made of layers of two-dimensional sheets. But HOIPs still preserve those desirable 2D quantum properties.”

Those sheets are held together by interspersed layers of another molecular structure that is a bit like a sheet of rubber bands. That makes the scaffolding wiggle like a funhouse floor.

“At room temperature, the molecules wiggle all over the place. That disrupts the lattice, which is where the electrons live. It’s really intense,” Silva said. “But surprisingly, the quantum properties are still really stable.”

Having quantum properties work at room temperature without requiring ultra-cooling is important for practical use as a semiconductor.

Going back to what HOIP stands for — hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites – this is how the experimental material fit into the HOIP chemical class: It was a hybrid of inorganic layers of a lead iodide (the rigid part) separated by organic layers (the rubber band-like parts) of phenylethylammonium (chemical formula (PEA)2PbI4).

The lead in this prototypical material could be swapped out for a metal safer for humans to handle before the development of an applicable material.

Electron choreography

HOIPs are great semiconductors because their electrons do an acrobatic square dance.

Usually, electrons live in an orbit around the nucleus of an atom or are shared by atoms in a chemical bond. But HOIP chemical lattices, like all semiconductors, are configured to share electrons more broadly.

Energy levels in a system can free the electrons to run around and participate in things like the flow of electricity and heat. The orbits, which are then empty, are called electron holes, and they want the electrons back.

“The hole is thought of as a positive charge, and of course, the electron has a negative charge,” Silva said. “So, hole and electron attract each other.”

The electrons and holes race around each other like dance partners pairing up to what physicists call an “exciton.” Excitons act and look a lot like particles themselves, though they’re not really particles.

Hopping biexciton light

In semiconductors, millions of excitons are correlated, or choreographed, with each other, which makes for desirable properties, when an energy source like electricity or laser light is applied. Additionally, excitons can pair up to form biexcitons, boosting the semiconductor’s energetic properties.

“In this material, we found that the biexciton binding energies were high,” Silva said. “That’s why we want to put this into lasers because the energy you input ends up to 80 or 90 percent as biexcitons.”

Biexcitons bump up energetically to absorb input energy. Then they contract energetically and pump out light. That would work not only in lasers but also in LEDs or other surfaces using the optoelectronic material.

“You can adjust the chemistry (of HOIPs) to control the width between biexciton states, and that controls the wavelength of the light given off,” Silva said. “And the adjustment can be very fine to give you any wavelength of light.”

That translates into any color of light the heart desires.

###

Coauthors of this paper were Stefanie Neutzner and Annamaria Petrozza from the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT); Daniele Cortecchia from IIT and Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore; Cesare Soci from the Centre for Disruptive Photonic Technologies, Singapore; Teddy Salim and Yeng Ming Lam from NTU; and Vlad Dragomir and Richard Leonelli from the University of Montreal. …

Three Canadian science funding agencies plus European and Singaporean science funding agencies but not one from the US ? That’s a bit unusual for research undertaken at a US educational institution.

This paper is behind a paywall.