Shrinky Dinks, a material used for children’s arts and crafts projects, has proved instrumental for developing a new technique to close the gap between nanowires. From a July 1, 2014 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

How do you put a puzzle together when the pieces are too tiny to pick up? Shrink the distance between them.

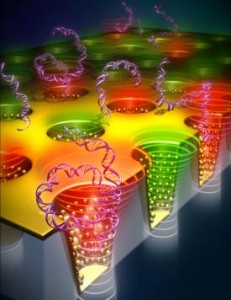

Engineers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign are using Shrinky Dinks, plastic that shrinks under high heat, to close the gap between nanowires in an array to make them useful for high-performance electronics applications. The group published its technique in the journal Nano Letters (“Assembly and Densification of Nanowire Arrays via Shrinkage”).

A July 1, 2014 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign news release, which originated the news item, provides more details about the new technique,

Nanowires are extremely fast, efficient semiconductors, but to be useful for electronics applications, they need to be packed together in dense arrays. Researchers have struggled to find a way to put large numbers of nanowires together so that they are aligned in the same direction and only one layer thick.

“Chemists have already done a brilliant job in making nanowires exhibit very high performance. We just don’t have a way to put them into a material that we can handle,” said study leader SungWoo Nam, a professor of mechanical science and engineering at the U. of I. “With the shrinking approach, people can make nanowires and nanotubes using any method they like and use the shrinking action to compact them into a higher density.”

The researchers place the nanowires on the Shrinky Dinks plastic as they would for any other substrate, but then shrink it to bring the wires much closer together. This allows them to create very dense arrays of nanowires in a simple, flexible and very controllable way.

The shrinking method has the added bonus of bringing the nanowires into alignment as they increase in density. Nam’s group demonstrated how even wires more than 30 degrees off-kilter can be brought into perfect alignment with their neighbors after shrinking.

“There’s assembly happening at the same time as the density increases,” Nam said, “so even if the wires are assembled in a disoriented direction we can still use this approach.”

The plastic is clamped before baking so that it only shrinks in one direction, so that the wires pack together but do not buckle. Clamping in different places could direct the arrays into interesting formations, according to Nam. The researchers also can control how densely the wires pack by varying the length of time the plastic is heated. They also are exploring using lasers to precisely shrink the plastic in specific patterns.

Nam first had the idea for using Shrinky Dinks plastic to assemble nanomaterials after seeing a microfluidics device that used channels made of shrinking plastic. He realized that the high degree of shrinking and the low cost of plastic could have a huge impact on nanowire assembly and processing for applications.

“I’m interested in this concept of synthesizing new materials that are assembled from nanoscale building blocks,” Nam said. “You can create new functions. For example, experiments have shown that film made of packed nanowires has properties that differ quite a bit from a crystal thin film.”

One application the group is now exploring is a thin film solar cell, made of densely packed nanowires, that could harvest energy from light much more efficiently than traditional thin-film solar cells.

I have featured the Shrinky Dinks product and its use for nanoscale fabrication before in an Aug. 16, 2010 posting which featured this reply from the lead researcher for that project on nanopatterning,

ETA Aug.17.10: I also contacted Teri W. Odom, professor at Northwestern University about why they use Slinky Dinks in their work. She very kindly responded with this:

Part of what we are interested in is the development of low-cost nanofabrication tools that can create macroscale areas of nanoscale patterns in a single step. For a variety of reasons, this end-product is hard to obtain—even though we and others have chipped away at this problem for years.

As an example, to achieve smaller and smaller separations between patterns, either expensive, top-down serial tools (such as electron beam lithography or scanning probe techniques) or bottom-up assembly methods need to be used. However, the former cannot easily create large areas of patterns, and the latter cannot readily control the separations of patterns.

We needed a way to obtain nanopatterns separated by specific distances on-demand. Here is where the Shrinky Dinks material comes in. My student had read a paper (published in 2007 in Lab on a Chip) about how this material was used to make microscale patterns starting from a pattern printed using a laser printer. I imagine his thought was: if this material could be used for microscale patterns, why not for nanoscale ones? It would be cheap, and it’s easy to order.

So, we combined this substrate with our new molding method—solvent assisted nanoscale embossing (SANE)—and could now heat the material to shrink the spacing between patterns. And thus, in some sense, we made available to any lab some of the capabilities of the billion-dollar nanofabrication industry for less than one-hundred dollars.

Getting back to this latest use of Shrinky Dinks, here’s a link to and a citation for the ‘nanowires’ research paper,

Assembly and Densification of Nanowire Arrays via Shrinkage by Jaehoon Bang, Jonghyun Choi, Fan Xia, Sun Sang Kwon, Ali Ashraf, Won Il Park, and SungWoo Nam. Nano Lett., 2014, 14 (6), pp 3304–3308 DOI: 10.1021/nl500709p Publication Date (Web): May 16, 2014

Copyright © 2014 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

* ‘dinks’ in headline changed to ‘Dinks’ on July 2, 2014 at 1150 hours PDT.