There’s a lot of excitement about nanoparticles as enabling a precise drug delivery system but to date results have been disappointing as a team of researchers at the University of Toronto (Canada) noted recently (see my April 27, 2016 posting). According to those researchers, one of the main problems with the proposed nanoparticle drug delivery system is that we don’t understand how the body delivers materials to cells and disappointingly few nanoparticles (less than 1%) make their way to tumours. That situation may be changing.

An Aug. 19, 2016 news item on Nanowerk announces the latest research from the University of Toronto,

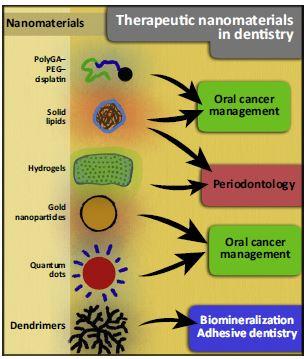

The emerging field of nanomedicine holds great promise in the battle against cancer. Particles the size of protein molecules can be customized to carry tumour-targeting drugs and destroy cancer cells without harming healthy tissue.

But here’s the problem: when nanoparticles are administered into the body, more than 99 per cent of them become trapped in non-targeted organs, such as the liver and spleen. These nanoparticles are not delivered to the site of action to carry out their intended function.

To solve this problem, researchers at the University of Toronto and the University Health Network have figured out how the liver and spleen trap intact nanoparticles as they move through the organ. “If you want to unlock the promise of nanoparticles, you have to understand and solve the problem of the liver,” says Dr. Ian McGilvray, a transplant surgeon at the Toronto General Hospital and scientist at the Toronto General Research Institute (TGRI).

An Aug. 15, 2016 University of Toronto news release by Luke Ng, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

In a recent paper in the journal Nature Materials, the researchers say that as nanoparticles move through the liver sinusoid, the flow rate slows down 1,000 times, which increases the interaction of the nanoparticles all of types of liver cells. This was a surprising finding because the current thought is that Kupffer cells, responsible for toxin breakdown in the liver, are the ones that gobbles [sic] up the particles. This study found that liver B-cells and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are also involved and that the cell phenotype also matters.

“We know that the liver is the principle organ controlling what gets absorbed by our bodies and what gets filtered out—it governs our everyday biological functions,” says Dr. Kim Tsoi (… [and] research partner Sonya MacParland), a U of T orthopaedic surgery resident, and a first author of the paper, who completed her PhD in biomedical engineering with Warren Chan (IBBME). “But nanoparticle drug delivery is a newer approach and we haven’t had a clear picture of how they interact with the liver—until now.”

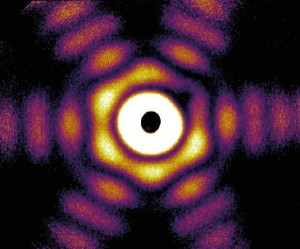

Tsoi and MacParland first examined both the speed and location of their engineered nanoparticles as they moved through the liver.

“This gives us a target to focus on,” says MacParland, an immunology post-doctoral fellow at U of T and TGRI. “Knowing the specific cells to modify will allow us to eventually deliver more of the nanoparticles to their intended target, attacking only the pathogens or tumours, while bypassing healthy cells.”

“Many prior studies that have tried to reduce nanomaterial clearance in the liver have focused on the particle design itself,” says Chan. “But our work now gives greater insight into the biological mechanisms underpinning our experimental observations — now we hope to use our fundamental findings to help design nanoparticles that work with the body, rather than against it.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Mechanism of hard-nanomaterial clearance by the liver by Kim M. Tsoi, Sonya A. MacParland, Xue-Zhong Ma, Vinzent N. Spetzler, Juan Echeverri, Ben Ouyang, Saleh M. Fadel, Edward A. Sykes, Nicolas Goldaracena, Johann M. Kaths, John B. Conneely, Benjamin A. Alman, Markus Selzner, Mario A. Ostrowski, Oyedele A. Adeyi, Anton Zilman, Ian D. McGilvray, & Warren C. W. Chan. Nature Materials (2016) doi:10.1038/nmat4718 Published online 15 August 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.

![Science: Ruining Everything Since 1543. It's true. Image credit: Zach Weiner [downloaded from http://www.slate.com/blogs/bad_astronomy/2013/01/23/saturday_morning_breakfast_cereal_new_science_book_of_web_comics.html]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Science-ruining-everything-300x184.jpeg)