I found some news about the Alberta technology scene in the programme for Japan’s nano tech 2017 exhibition and conference to be held Feb. 15 – 17, 2017 in Tokyo. First, here’s more about the show in Japan from a Jan. 17, 2017 nano tech 2017 press release on Business Wire (also on Yahoo News),

The nano tech executive committee (chairman: Tomoji Kawai, Specially Appointed Professor, Osaka University) will be holding “nano tech 2017” – one of the world’s largest nanotechnology exhibitions, now in its 16th year – on February 15, 2017, at the Tokyo Big Sight convention center in Japan. 600 organizations (including over 40 first-time exhibitors) from 23 countries and regions are set to exhibit at the event in 1,000 booths, demonstrating revolutionary and cutting edge core technologies spanning such industries as automotive, aerospace, environment/energy, next-generation sensors, cutting-edge medicine, and more. Including attendees at the concurrently held exhibitions, the total number of visitors to the event is expected to exceed 50,000.

The theme of this year’s nano tech exhibition is “Open Nano Collaboration.” By bringing together organizations working in a wide variety of fields, the business matching event aims to promote joint development through cross-field collaboration.

Special Symposium: “Nanotechnology Contributing to the Super Smart Society”

Each year nano tech holds Special Symposium, in which industry specialists from top organizations from Japan and abroad speak about the issues surrounding the latest trends in nanotech. The themes of this year’s Symposium are Life Nanotechnology, Graphene, AI/IoT, Cellulose Nanofibers, and Materials Informatics.

Notable sessions include:

Life Nanotechnology

“Development of microRNA liquid biopsy for early detection of cancer”

Takahiro Ochiya, National Cancer Center Research Institute Division of Molecular and Cellular Medicine, ChiefAI / IoT

“AI Embedded in the Real World”

Hideki Asoh, AIST Deputy Director, Artificial Intelligence Research CenterCellulose Nanofibers [emphasis mine]

“The Current Trends and Challenges for Industrialization of Nanocellulose”

Satoshi Hirata, Nanocellulose Forum Secretary-GeneralMaterials Informatics

“Perspective of Materials Research”

Hideo Hosono, Tokyo Institute of Technology ProfessorView the full list of sessions:

>> http://nanotech2017.icsbizmatch.jp/Presentation/en/Info/List#main_theaternano tech 2017 Homepage:

>> http://nanotechexpo.jp/nano tech 2017, the 16th International Nanotechnology Exhibition & Conference

Date: February 15-17, 2017, 10:00-17:00

Venue: Tokyo Big Sight (East Halls 4-6 & Conference Tower)

Organizer: nano tech Executive Committee, JTB Communication Design

As you may have guessed the Alberta information can be found in the .Cellulose Nanofibers session. From the conference/seminar program page; scroll down about 25% of the way to find the Alberta presentation,

Production and Applications Development of Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC) at InnoTech Alberta

Behzad (Benji) Ahvazi

InnoTech Alberta Team Lead, Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC)[ Abstract ]

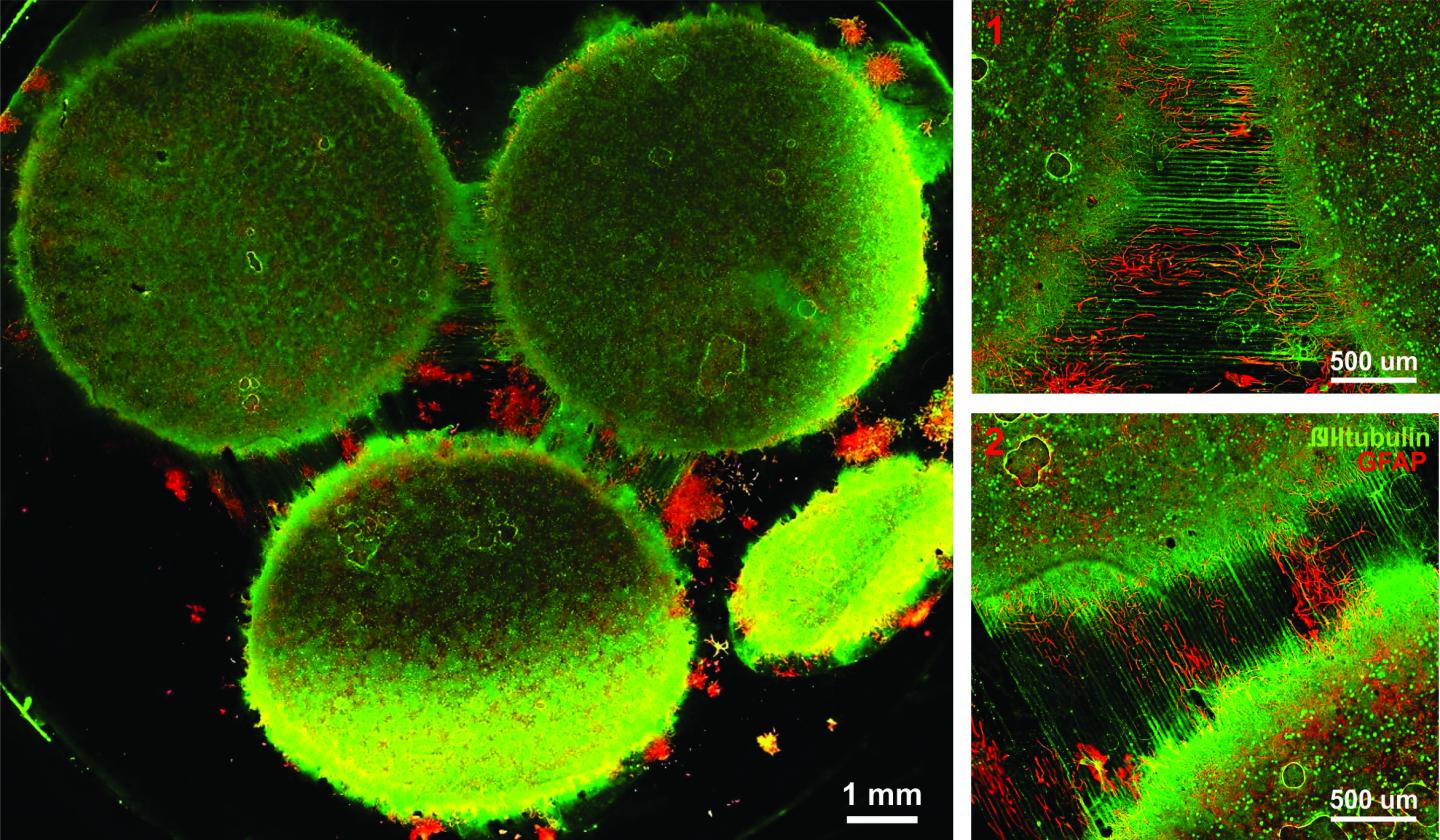

The production and use of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) is an emerging technology that has gained considerable interest from a range of industries that are working towards increased use of “green” biobased materials. The construction of one-of-a-kind CNC pilot plant [emphasis mine] at InnoTech Alberta and production of CNC samples represents a critical step for introducing the cellulosic based biomaterials to industrial markets and provides a platform for the development of novel high value and high volume applications. Major key components including feedstock, acid hydrolysis formulation, purification, and drying processes were optimized significantly to reduce the operation cost. Fully characterized CNC samples were provided to a large number of academic and research laboratories including various industries domestically and internationally for applications development.

[ Profile ]

Dr. Ahvazi completed his Bachelor of Science in Honours program at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and graduated with distinction at Concordia University in Montréal, Québec. His Ph.D. program was completed in 1998 at McGill Pulp and Paper Research Centre in the area of macromolecules with solid background in Lignocellulosic, organic wood chemistry as well as pulping and paper technology. After completing his post-doctoral fellowship, he joined FPInnovations formally [formerly?] known as PAPRICAN as a research scientist (R&D) focusing on a number of confidential chemical pulping and bleaching projects. In 2006, he worked at Tembec as a senior research scientist and as a Leader in Alcohol and Lignin (R&D). In April 2009, he held a position as a Research Officer in both National Bioproducts (NBP1 & NBP2) and Industrial Biomaterials Flagship programs at National Research Council Canada (NRC). During his tenure, he had directed and performed innovative R&D activities within both programs on extraction, modification, and characterization of biomass as well as polymer synthesis and formulation for industrial applications. Currently, he is working at InnoTech Alberta as Team Lead for Biomass Conversion and Processing Technologies.

Canada scene update

InnoTech Alberta was until Nov. 1, 2016 known as Alberta Innovates – Technology Futures. Here’s more about InnoTech Alberta from the Alberta Innovates … home page,

Effective November 1, 2016, Alberta Innovates – Technology Futures is one of four corporations now consolidated into Alberta Innovates and a wholly owned subsidiary called InnoTech Alberta.

You will find all the existing programs, services and information offered by InnoTech Alberta on this website. To access the basic research funding and commercialization programs previously offered by Alberta Innovates – Technology Futures, explore here. For more information on Alberta Innovates, visit the new Alberta Innovates website.

As for InnoTech Alberta’s “one-of-a-kind CNC pilot plant,” I’d like to know more about it’s one-of-a-kind status since there are two other CNC production plants in Canada. (Is the status a consequence of regional chauvinism or a writer unfamiliar with the topic?). Getting back to the topic, the largest company (and I believe the first) with a CNC plant was CelluForce, which started as a joint venture between Domtar and FPInnovations and powered with some very heavy investment from the government of Canada. (See my July 16, 2010 posting about the construction of the plant in Quebec and my June 6, 2011 posting about the newly named CelluForce.) Interestingly, CelluForce will have a booth at nano tech 2017 (according to its Jan. 27, 2017 news release) although the company doesn’t seem to have any presentations on the schedule. The other Canadian company is Blue Goose Biorefineries in Saskatchewan. Here’s more about Blue Goose from the company website’s home page,

Blue Goose Biorefineries Inc. (Blue Goose) is pleased to introduce our R3TM process. R3TM technology incorporates green chemistry to fractionate renewable plant biomass into high value products.

Traditionally, separating lignocellulosic biomass required high temperatures, harsh chemicals, and complicated processes. R3TM breaks this costly compromise to yield high quality cellulose, lignin and hemicellulose products.

The robust and environmentally friendly R3TM technology has numerous applications. Our current product focus is cellulose nanocrystals (CNC). Cellulose nanocrystals are “Mother Nature’s Building Blocks” possessing unique properties. These unique properties encourage the design of innovative products from a safe, inherently renewable, sustainable, and carbon neutral resource.

Blue Goose assists companies and research groups in the development of applications for CNC, by offering CNC for sale without Intellectual Property restrictions. [emphasis mine]

Bravo to Blue Goose! Unfortunately, I was not able to determine if the company will be at nano tech 2017.

One final comment, there was some excitement about CNC a while back where I had more than one person contact me asking for information about how to buy CNC. I wasn’t able to be helpful because there was, apparently, an attempt by producers to control sales and limit CNC access to a select few for competitive advantage. Coincidentally or not, CelluForce developed a stockpile which has persisted for some years as I noted in my Aug. 17, 2016 posting (scroll down about 70% of the way) where the company announced amongst other events that it expected deplete its stockpile by mid-2017.