It’s still theory at this point but researchers at Brown University (Rhode Island, US) have produced experimental proof that a single layer of boron atoms in a lattice reminiscent of but not identical to a graphene layer is possible. A Jan. 28, 2014 news item on Azonano describes the research,

Researchers from Brown University have shown experimentally that a boron-based competitor to graphene is a very real possibility.

Graphene has been heralded as a wonder material. Made of a single layer of carbon atoms in a honeycomb arrangement, graphene is stronger pound-for-pound than steel and conducts electricity better than copper. Since the discovery of graphene, scientists have wondered if boron, carbon’s neighbor on the periodic table, could also be arranged in single-atom sheets. Theoretical work suggested it was possible, but the atoms would need to be in a very particular arrangement.

Boron has one fewer electron than carbon and as a result can’t form the honeycomb lattice that makes up graphene. For boron to form a single-atom layer, theorists suggested that the atoms must be arranged in a triangular lattice with hexagonal vacancies — holes — in the lattice.

“That was the prediction,” said Lai-Sheng Wang, professor of chemistry at Brown, “but nobody had made anything to show that’s the case.”

Wang and his research group, which has studied boron chemistry for many years, have now produced the first experimental evidence that such a structure is possible. In a paper published on January 20 in Nature Communications, Wang and his team showed that a cluster made of 36 boron atoms (B36) forms a symmetrical, one-atom thick disc with a perfect hexagonal hole in the middle.

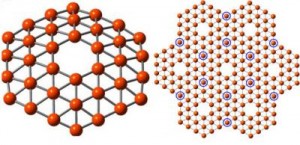

Here’s an image that illustrates ‘borophene’,

Caption: This shows a 36-atom cluster of boron, left, arranged as a flat disc with a hexagonal hole in the middle, fits the theoretical requirements for making a one-atom-thick boron sheet, right, a theoretical nanomaterial dubbed “borophene.”

Credit: Wang Lab / Brown University

The Jan. 27, 2014 Brown University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides details about how the research was conducted,

The work required a combination of laboratory experiments and computational modeling. In the lab, Wang and his student, Wei-Li Li, probe the properties of boron clusters using a technique called photoelectron spectroscopy. They start by zapping chunks of bulk boron with a laser to create vapor of boron atoms. A jet of helium then freezes the vapor into tiny clusters of atoms. Those clusters are then zapped with a second laser, which knocks an electron out of the cluster and sends it flying down a long tube that Wang calls his “electron racetrack.” The speed at which the electron flies down the racetrack is used to determine the cluster’s electron binding energy spectrum — a readout of how tightly the cluster holds its electrons. That spectrum serves as fingerprint of the cluster’s structure.

Wang’s experiments showed that the B36 cluster was something special. It had an extremely low electron binding energy compared to other boron clusters. The shape of the cluster’s binding spectrum also suggested that it was a symmetrical structure.

To find out exactly what that structure might look like, Wang turned to Zachary Piazza, one of his graduate students specializing in computational chemistry. Piazza began modeling potential structures for B36 on a supercomputer, investigating more than 3,000 possible arrangements of those 36 atoms. Among the arrangements that would be stable was the planar disc with the hexagonal hole.

“As soon as I saw that hexagonal hole,” Wang said, “I told Zach, ‘We have to investigate that.'”

To ensure that they have truly found the most stable arrangement of the 36 boron atoms, they enlisted the help of Jun Li, who is a professor of chemistry at Tsinghua University in Beijing and a former senior research scientist at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) in Richland, Wash. Li, a longtime collaborator of Wang’s, has developed a new method of finding stable structures of clusters, which would be suitable for the job at hand. Piazza spent the summer of 2013 at PNNL working with Li and his students on the B36 project. They used the supercomputer at PNNL to examine more possible arrangements of the 36 boron atoms and compute their electron binding spectra. They found that the planar disc with a hexagonal hole matched very closely with the spectrum measured in the lab experiments, indicating that the structure Piazza found initially on the computer was indeed the structure of B36.

That structure also fits the theoretical requirements for making borophene, which is an extremely interesting prospect, Wang said. The boron-boron bond is very strong, nearly as strong as the carbon-carbon bond. So borophene should be very strong. Its electrical properties may be even more interesting. Borophene is predicted to be fully metallic, whereas graphene is a semi-metal. That means borophene might end up being a better conductor than graphene.

“That is,” Wang cautions, “if anyone can make it.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the research paper,

Planar hexagonal B36 as a potential basis for extended single-atom layer boron sheets by Zachary A. Piazza, Han-Shi Hu, Wei-Li Li, Ya-Fan Zhao, Jun Li, & Lai-Sheng Wang. Nature Communications 5, Article number: 3113 doi:10.1038/ncomms4113 Published 20 January 2014

This paper is behind a paywall.