It seems the Center for the Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (CEINT) at Duke University (North Carolina, US) is making an adjustment to its focus and opening the door to industry, as well as, government research. It has for some years (my first post about the CEINT at Duke University is an Aug. 15, 2011 post about its mesocosms) been focused on examining the impact of nanoparticles (also called nanomaterials) on plant life and aquatic systems. This Jan. 9, 2017 US National Science Foundation (NSF) news release (h/t Jan. 9, 2017 Nanotechnology Now news item) provides a general description of the work,

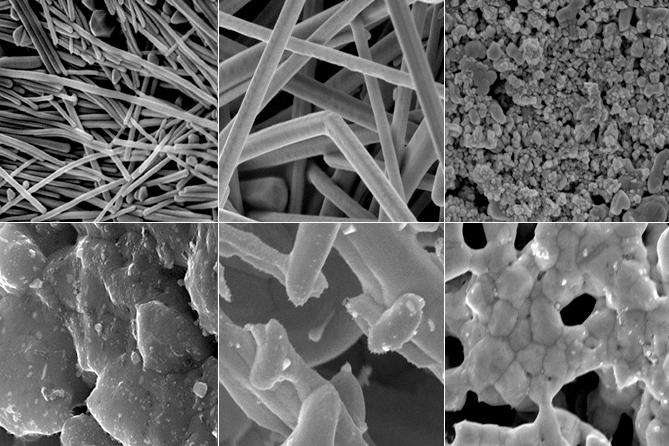

We can’t see them, but nanomaterials, both natural and manmade, are literally everywhere, from our personal care products to our building materials–we’re even eating and drinking them.

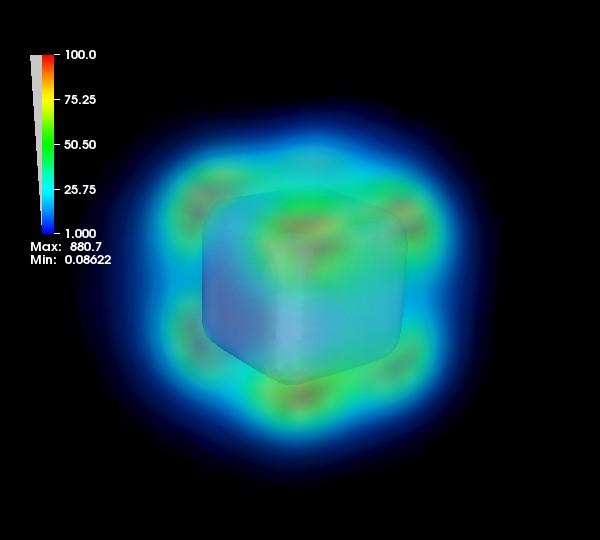

At the NSF-funded Center for Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (CEINT), headquartered at Duke University, scientists and engineers are researching how some of these nanoscale materials affect living things. One of CEINT’s main goals is to develop tools that can help assess possible risks to human health and the environment. A key aspect of this research happens in mesocosms, which are outdoor experiments that simulate the natural environment – in this case, wetlands. These simulated wetlands in Duke Forest serve as a testbed for exploring how nanomaterials move through an ecosystem and impact living things.

CEINT is a collaborative effort bringing together researchers from Duke, Carnegie Mellon University, Howard University, Virginia Tech, University of Kentucky, Stanford University, and Baylor University. CEINT academic collaborations include on-going activities coordinated with faculty at Clemson, North Carolina State and North Carolina Central universities, with researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Environmental Protection Agency labs, and with key international partners.

The research in this episode was supported by NSF award #1266252, Center for the Environmental Implications of NanoTechnology.

The mention of industry is in this video by O’Brien and Kellan, which describes CEINT’s latest work ,

Somewhat similar in approach although without a direction reference to industry, Canada’s Experimental Lakes Area (ELA) is being used as a test site for silver nanoparticles. Here’s more from the Distilling Science at the Experimental Lakes Area: Nanosilver project page,

Water researchers are interested in nanotechnology, and one of its most commonplace applications: nanosilver. Today these tiny particles with anti-microbial properties are being used in a wide range of consumer products. The problem with nanoparticles is that we don’t fully understand what happens when they are released into the environment.

The research at the IISD-ELA [International Institute for Sustainable Development Experimental Lakes Area] will look at the impacts of nanosilver on ecosystems. What happens when it gets into the food chain? And how does it affect plants and animals?

Here’s a video describing the Nanosilver project at the ELA,

You may have noticed a certain tone to the video and it is due to some political shenanigans, which are described in this Aug. 8, 2016 article by Bartley Kives for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC) online news.

![Fig. 1: A Vigna radiata seeds. b Reddish brown solution of silver nanoparticles formed after 3 h due to reduction of silver ions [downloaded from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13204-015-0418-6]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/India_SilverNanoparrticles_MungBean.gif)