Given that it’s summer, I seem to be increasingly obsessed with windows that help control the heat from the sun. So, this Aug. 22, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily hit my sweet spot,

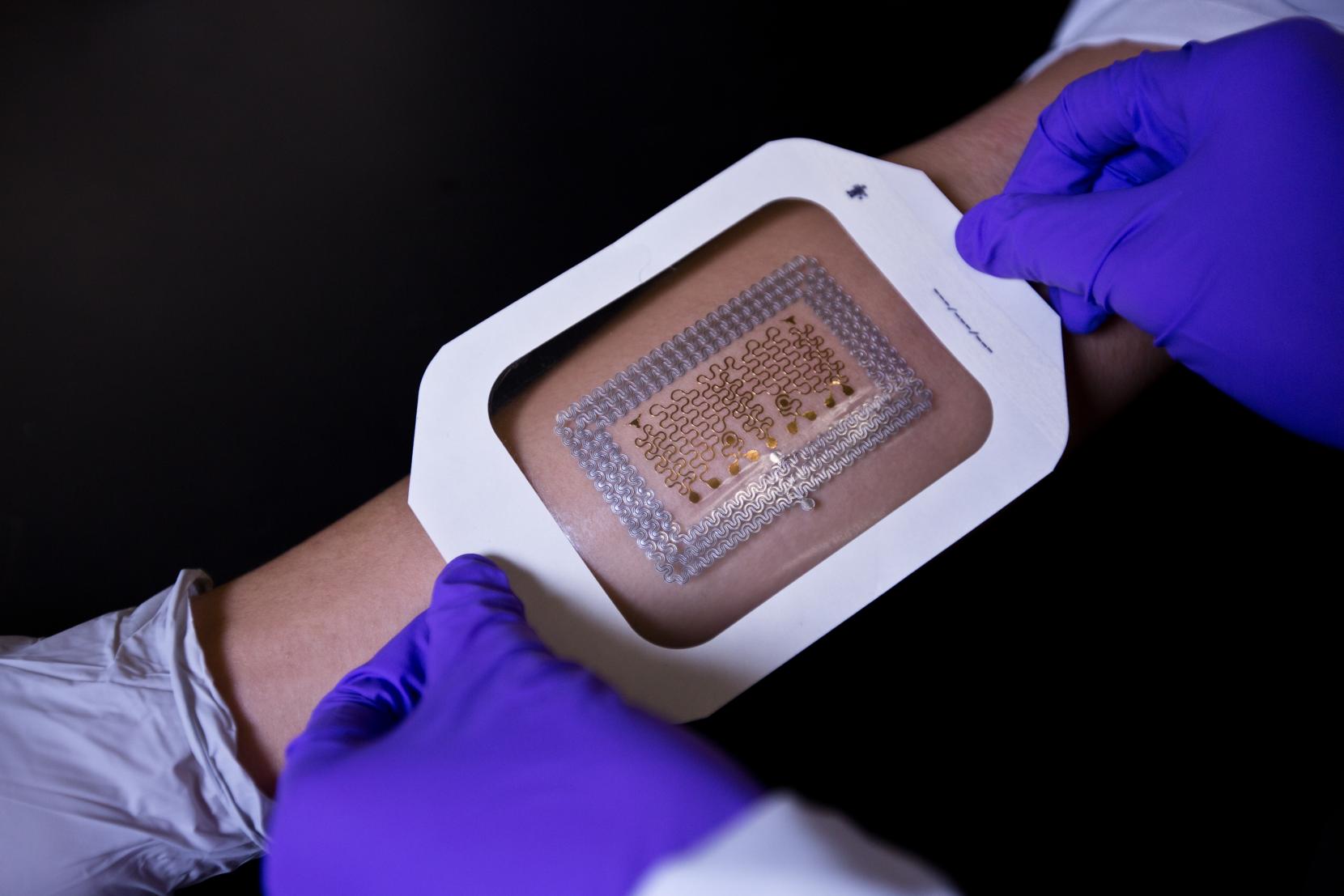

Researchers in the Cockrell School of Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin have invented a new flexible smart window material that, when incorporated into windows, sunroofs, or even curved glass surfaces, will have the ability to control both heat and light from the sun. …

Delia Milliron, an associate professor in the McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, and her team’s advancement is a new low-temperature process for coating the new smart material on plastic, which makes it easier and cheaper to apply than conventional coatings made directly on the glass itself. The team demonstrated a flexible electrochromic device, which means a small electric charge (about 4 volts) can lighten or darken the material and control the transmission of heat-producing, near-infrared radiation. Such smart windows are aimed at saving on cooling and heating bills for homes and businesses.

An Aug. 22, 2016 University of Texas at Austin news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the international team behind this research and offers more details about the research itself,

The research team is an international collaboration, including scientists at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and CNRS in France, and Ikerbasque in Spain. Researchers at UT Austin’s College of Natural Sciences provided key theoretical work.

Milliron and her team’s low-temperature process generates a material with a unique nanostructure, which doubles the efficiency of the coloration process compared with a coating produced by a conventional high-temperature process. It can switch between clear and tinted more quickly, using less power.

The new electrochromic material, like its high-temperature processed counterpart, has an amorphous structure, meaning the atoms lack any long-range organization as would be found in a crystal. However, the new process yields a unique local arrangement of the atoms in a linear, chain-like structure. Whereas conventional amorphous materials produced at high temperature have a denser three-dimensionally bonded structure, the researchers’ new linearly structured material, made of chemically condensed niobium oxide, allows ions to flow in and out more freely. As a result, it is twice as energy efficient as the conventionally processed smart window material.

At the heart of the team’s study is their rare insight into the atomic-scale structure of the amorphous materials, whose disordered structures are difficult to characterize. Because there are few techniques for characterizing the atomic-scale structure sufficiently enough to understand properties, it has been difficult to engineer amorphous materials to enhance their performance.

“There’s relatively little insight into amorphous materials and how their properties are impacted by local structure,” Milliron said. “But, we were able to characterize with enough specificity what the local arrangement of the atoms is, so that it sheds light on the differences in properties in a rational way.”

Graeme Henkelman, a co-author on the paper and chemistry professor in UT Austin’s College of Natural Sciences, explains that determining the atomic structure for amorphous materials is far more difficult than for crystalline materials, which have an ordered structure. In this case, the researchers were able to use a combination of techniques and measurements to determine an atomic structure that is consistent in both experiment and theory.

“Such collaborative efforts that combine complementary techniques are, in my view, the key to the rational design of new materials,” Henkelman said.

Milliron believes the knowledge gained here could inspire deliberate engineering of amorphous materials for other applications such as supercapacitors that store and release electrical energy rapidly and efficiently.

The Milliron lab’s next challenge is to develop a flexible material using their low-temperature process that meets or exceeds the best performance of electrochromic materials made by conventional high-temperature processing.

“We want to see if we can marry the best performance with this new low-temperature processing strategy,” she said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Linear topology in amorphous metal oxide electrochromic networks obtained via low-temperature solution processing by Anna Llordés, Yang Wang, Alejandro Fernandez-Martinez, Penghao Xiao, Tom Lee, Agnieszka Poulain, Omid Zandi, Camila A. Saez Cabezas, Graeme Henkelman, & Delia J. Milliron. Nature Materials (2016) doi:10.1038/nmat4734 Published online 22 August 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.