In a February 13, 2023 essay, Michael Berger who runs the Nanowerk website provides an overview of brainlike (neuromorphic) engineering.

This essay is the most extensive piece I’ve seen on Berger’s website and it covers everything from the reasons why scientists are so interested in mimicking the human brain to specifics about memristors. Here are a few excerpts (Note: Links have been removed),

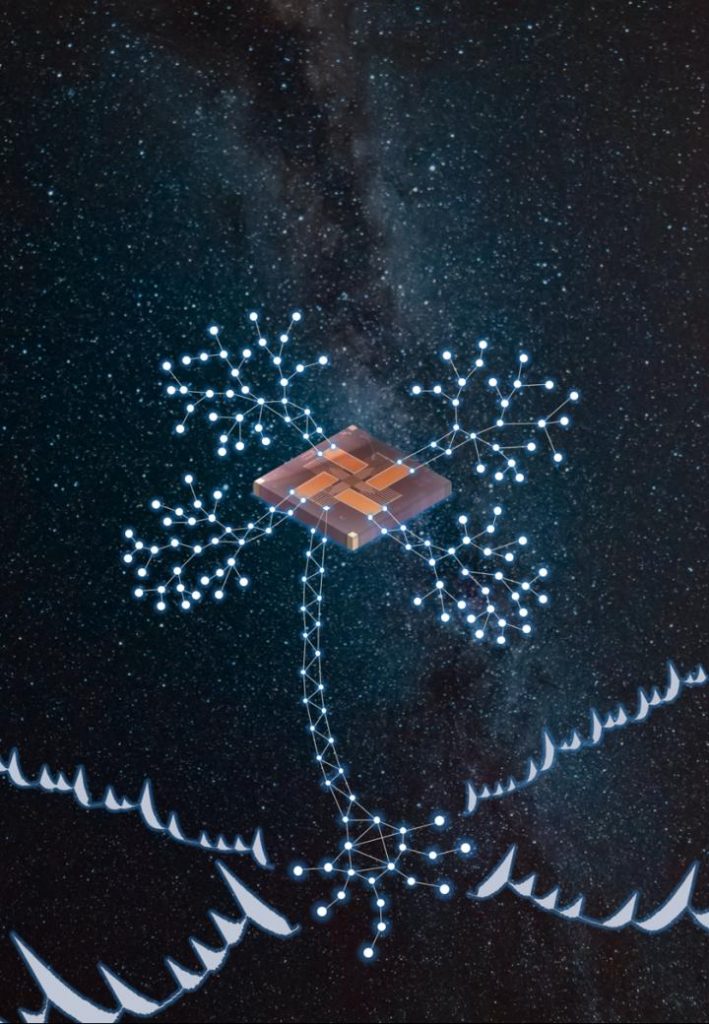

Neuromorphic engineering is a cutting-edge field that focuses on developing computer hardware and software systems inspired by the structure, function, and behavior of the human brain. The ultimate goal is to create computing systems that are significantly more energy-efficient, scalable, and adaptive than conventional computer systems, capable of solving complex problems in a manner reminiscent of the brain’s approach.

This interdisciplinary field draws upon expertise from various domains, including neuroscience, computer science, electronics, nanotechnology, and materials science. Neuromorphic engineers strive to develop computer chips and systems incorporating artificial neurons and synapses, designed to process information in a parallel and distributed manner, akin to the brain’s functionality.

Key challenges in neuromorphic engineering encompass developing algorithms and hardware capable of performing intricate computations with minimal energy consumption, creating systems that can learn and adapt over time, and devising methods to control the behavior of artificial neurons and synapses in real-time.

Neuromorphic engineering has numerous applications in diverse areas such as robotics, computer vision, speech recognition, and artificial intelligence. The aspiration is that brain-like computing systems will give rise to machines better equipped to tackle complex and uncertain tasks, which currently remain beyond the reach of conventional computers.

It is essential to distinguish between neuromorphic engineering and neuromorphic computing, two related but distinct concepts. Neuromorphic computing represents a specific application of neuromorphic engineering, involving the utilization of hardware and software systems designed to process information in a manner akin to human brain function.

…

One of the major obstacles in creating brain-inspired computing systems is the vast complexity of the human brain. Unlike traditional computers, the brain operates as a nonlinear dynamic system that can handle massive amounts of data through various input channels, filter information, store key information in short- and long-term memory, learn by analyzing incoming and stored data, make decisions in a constantly changing environment, and do all of this while consuming very little power.

…

The Human Brain Project [emphasis mine], a large-scale research project launched in 2013, aims to create a comprehensive, detailed, and biologically realistic simulation of the human brain, known as the Virtual Brain. One of the goals of the project is to develop new brain-inspired computing technologies, such as neuromorphic computing.

…

The Human Brain Project has been funded by the European Union (1B Euros over 10 years starting in 2013 and sunsetting in 2023). From the Human Brain Project Media Invite,

The final Human Brain Project Summit 2023 will take place in Marseille, France, from March 28-31, 2023.

As the ten-year European Flagship Human Brain Project (HBP) approaches its conclusion in September 2023, the final HBP Summit will highlight the scientific achievements of the project at the interface of neuroscience and technology and the legacy that it will leave for the brain research community. …

One last excerpt from the essay,

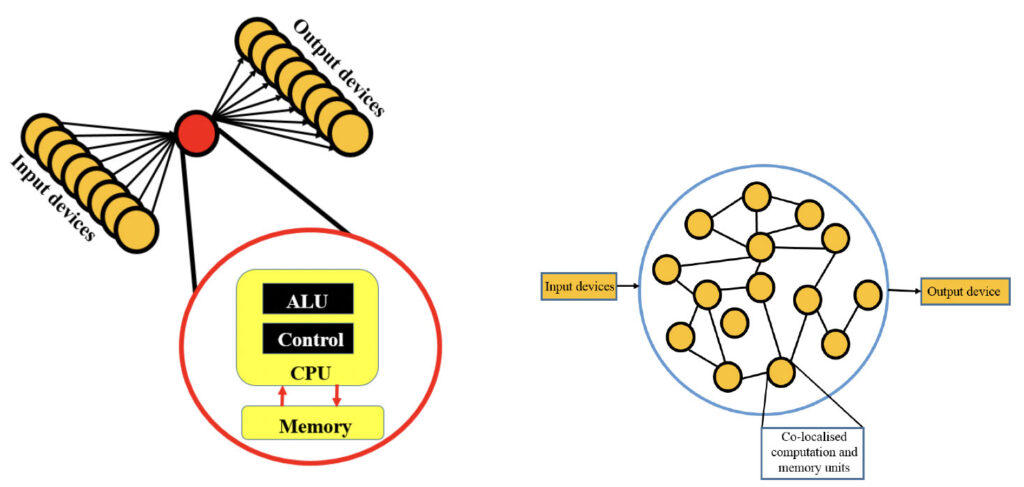

Neuromorphic computing is a radical reimagining of computer architecture at the transistor level, modeled after the structure and function of biological neural networks in the brain. This computing paradigm aims to build electronic systems that attempt to emulate the distributed and parallel computation of the brain by combining processing and memory in the same physical location.

This is unlike traditional computing, which is based on von Neumann systems consisting of three different units: processing unit, I/O unit, and storage unit. This stored program architecture is a model for designing computers that uses a single memory to store both data and instructions, and a central processing unit to execute those instructions. This design, first proposed by mathematician and computer scientist John von Neumann, is widely used in modern computers and is considered to be the standard architecture for computer systems and relies on a clear distinction between memory and processing.

…

I found the diagram Berger Included with von Neumann’s design contrasted with a neuromorphic design illuminating,

Berger offers a very good overview and I recommend reading his February 13, 2023 essay on neuromorphic engineering with one proviso, Note: A link has been removed,

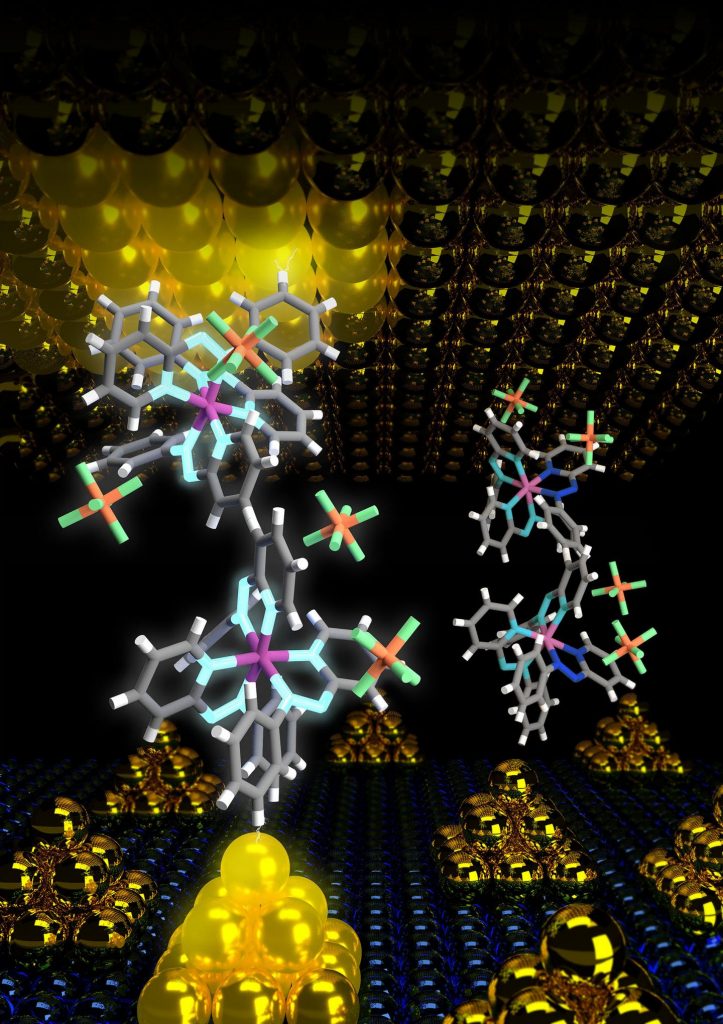

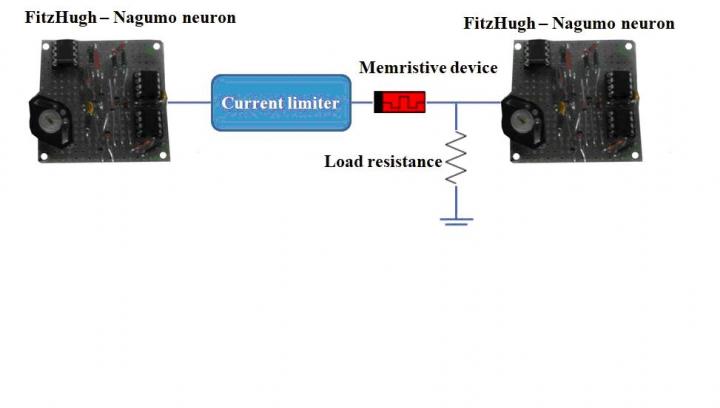

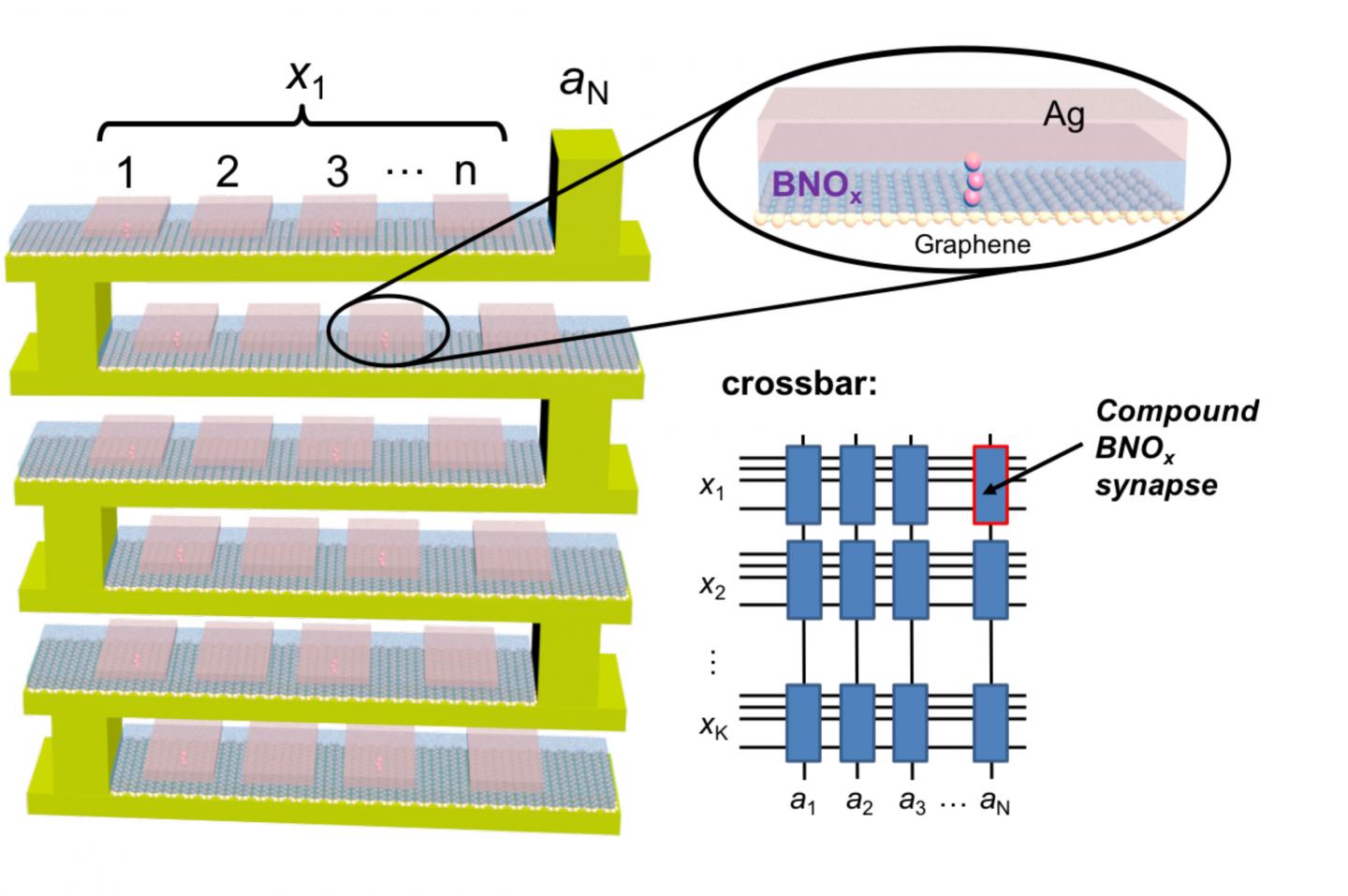

Many researchers in this field see memristors as a key device component for neuromorphic engineering. Memristor – or memory resistor – devices are non-volatile nanoelectronic memory devices that were first theorized [emphasis mine] by Leon Chua in the 1970’s. However, it was some thirty years later that the first practical device was fabricated in 2008 by a group led by Stanley Williams [sometimes cited as R. Stanley Williams] at HP Research Labs.

…

Chua wasn’t the first as he, himself, has noted. Chua arrived at his theory independently in the 1970s but Bernard Widrow theorized what he called a ‘memistor’ in the 1960s. In fact “Memristors: they are older than you think” is a May 22, 2012 posting which featured an article “Two centuries of memristors” by Themistoklis Prodromakis, Christofer Toumazou and Leon Chua published in Nature Materials.

Most of us try to get it right but we don’t always succeed. It’s always good practice to read everyone (including me) with a little skepticism.