Generally I expect robots to be machines that are external to my body but recently there were two news bits about some different approaches. First, the wearable robot.

A robot that supports your hip

A January 10, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily describes research into muscles that can be worn,

Scientists are one step closer to artificial muscles. Orthotics have come a long way since their initial wood and strap designs, yet innovation lapsed when it came to compensating for muscle power — until now.

A collaborative research team has designed a wearable robot to support a person’s hip joint while walking. The team, led by Minoru Hashimoto, a professor of textile science and technology at Shinshu University in Japan, published the details of their prototype in Smart Materials and Structures, a journal published by the Institute of Physics.

A January 9, 2018 Shinshu University press release on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

“With a rapidly aging society, an increasing number of elderly people require care after suffering from stroke, and other-age related disabilities. Various technologies, devices, and robots are emerging to aid caretakers,” wrote Hashimoto, noting that several technologies meant to assist a person with walking are often cumbersome to the user. “[In our] current study, [we] sought to develop a lightweight, soft, wearable assist wear for supporting activities of daily life for older people with weakened muscles and those with mobility issues.”

The wearable system consists of plasticized polyvinyl chloride (PVC) gel, mesh electrodes, and applied voltage. The mesh electrodes sandwich the gel, and when voltage is applied, the gel flexes and contracts, like a muscle. It’s a wearable actuator, the mechanism that causes movement.

“We thought that the electrical mechanical properties of the PVC gel could be used for robotic artificial muscles, so we started researching the PVC gel,” said Hashimoto. “The ability to add voltage to PVC gel is especially attractive for high speed movement, and the gel moves with high speed with just a few hundred volts.”

In a preliminary evaluation, a stroke patient with some paralysis on one side of his body walked with and without the wearable system.

“We found that the assist wear enabled natural movement, increasing step length and decreasing muscular activity during straight line walking,” wrote Hashimoto. The researchers also found that adjusting the charge could change the level of assistance the actuator provides.

The robotic system earned first place in demonstrations with their multilayer PVC gel artificial muscle at the, “24th International Symposium on Smart Structures and Materials & Nondestructive Evaluation and Health Monitoring” for SPIE the international society for optics and photonics.

Next, the researchers plan to create a string actuator using the PVC gel, which could potentially lead to the development of fabric capable of providing more manageable external muscular support with ease.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

PVC gel soft actuator-based wearable assist wear for hip joint support during walking by Yi Li and Minoru Hashimoto. Smart Materials and Structures, Volume 26, Number 12 DOI: 10.1088/1361-665X/aa9315 Published 30 October 2017

© 2017 IOP Publishing Ltd

This paper is behind a paywall and I see it was published in the Fall of 2017. Either they postponed the publicity or this is the second wave. In any event, it was timely as it allowed me to post this along with the robotic research on regeneration.

Robotic implants and tissue regeneration

Boston Children’s Hospital in a January 10, 2018 news release on EurekAlert describes a new (to me) method for tissue regeneration,

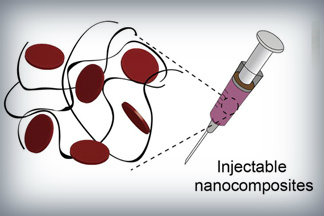

An implanted, programmable medical robot can gradually lengthen tubular organs by applying traction forces — stimulating tissue growth in stunted organs without interfering with organ function or causing apparent discomfort, report researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital.

The robotic system, described today in Science Robotics, induced cell proliferation and lengthened part of the esophagus in a large animal by about 75 percent, while the animal remained awake and mobile. The researchers say the system could treat long-gap esophageal atresia, a rare birth defect in which part of the esophagus is missing, and could also be used to lengthen the small intestine in short bowel syndrome.

The most effective current operation for long-gap esophageal atresia, called the Foker process, uses sutures anchored on the patient’s back to gradually pull on the esophagus. To prevent the esophagus from tearing, patients must be paralyzed in a medically induced coma and placed on mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit for one to four weeks. The long period of immobilization can also cause medical complications such as bone fractures and blood clots.

“This project demonstrates proof-of-concept that miniature robots can induce organ growth inside a living being for repair or replacement, while avoiding the sedation and paralysis currently required for the most difficult cases of esophageal atresia,” says Russell Jennings, MD, surgical director of the Esophageal and Airway Treatment Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, and a co-investigator on the study. “The potential uses of such robots are yet to be fully explored, but they will certainly be applied to many organs in the near future.”

The motorized robotic device is attached only to the esophagus, so would allow a patient to move freely. Covered by a smooth, biocompatible, waterproof “skin,” it includes two attachment rings, placed around the esophagus and sewn into place with sutures. A programmable control unit outside the body applies adjustable traction forces to the rings, slowly and steadily pulling the tissue in the desired direction.

The device was tested in the esophagi of pigs (five received the implant and three served as controls). The distance between the two rings (pulling the esophagus in opposite directions) was increased by small, 2.5-millimeter increments each day for 8 to 9 days. The animals were able to eat normally even with the device applying traction to its esophagus, and showed no sign of discomfort.

On day 10, the segment of esophagus had increased in length by 77 percent on average. Examination of the tissue showed a proliferation of the cells that make up the esophagus. The organ also maintained its normal diameter.

“This shows we didn’t simply stretch the esophagus — it lengthened through cell growth,” says Pierre Dupont, PhD, the study’s senior investigator and Chief of Pediatric Cardiac Bioengineering at Boston Children’s.

The research team is now starting to test the robotic system in a large animal model of short bowel syndrome. While long-gap esophageal atresia is quite rare, the prevalence of short bowel syndrome is much higher. Short bowel can be caused by necrotizing enterocolitis in the newborn, Crohn’s disease in adults, or a serious infection or cancer requiring a large segment of intestine to be removed.

“Short bowel syndrome is a devastating illness requiring patients to be fed intravenously,” says gastroenterologist Peter Ngo, MD, a coauthor on the study. “This, in turn, can lead to liver failure, sometimes requiring a liver or multivisceral (liver-intestine) transplant, outcomes that are both devastating and costly.”

The team hopes to get support to continue its tests of the device in large animal models, and eventually conduct clinical trials. They will also test other features.

“No one knows the best amount of force to apply to an organ to induce growth,” explains Dupont. “Today, in fact, we don’t even know what forces we are applying clinically. It’s all based on surgeon experience. A robotic device can figure out the best forces to apply and then apply those forces precisely.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

In vivo tissue regeneration with robotic implants by Dana D. Damian, Karl Price, Slava Arabagi, Ignacio Berra, Zurab Machaidze, Sunil Manjila, Shogo Shimada, Assunta Fabozzo, Gustavo Arnal, David Van Story, Jeffrey D. Goldsmith, Agoston T. Agoston, Chunwoo Kim, Russell W. Jennings, Peter D. Ngo, Michael Manfredi, and Pierre E. Dupont. Science Robotics 10 Jan 2018: Vol. 3, Issue 14, eaaq0018 DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.aaq0018

This paper is behind a paywall.