Scientists, He Jiankui and Michael Deem, may have created the first human babies born after being subjected to CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) gene editing. At this point, no one is entirely certain that these babies as described actually exist since the information was made public in a rather unusual (for scientists) fashion.

The news broke on Sunday, November 25, 2018 through a number of media outlets none of which included journals associated with gene editing or high impact journals such as Cell, Nature, or Science.The news broke in MIT Technology Review and in Associated Press. Plus, this all happened just before the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing (Nov. 27 – 29, 2018) in Hong Kong. He Jiankui was scheduled to speak today, Nov. 27, 2018.

Predictably, this news has caused quite a tizzy.

Breaking news

Antonio Regalado broke the news in a November 25, 2018 article for MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] Technology Review (Note: Links have been removed),

…

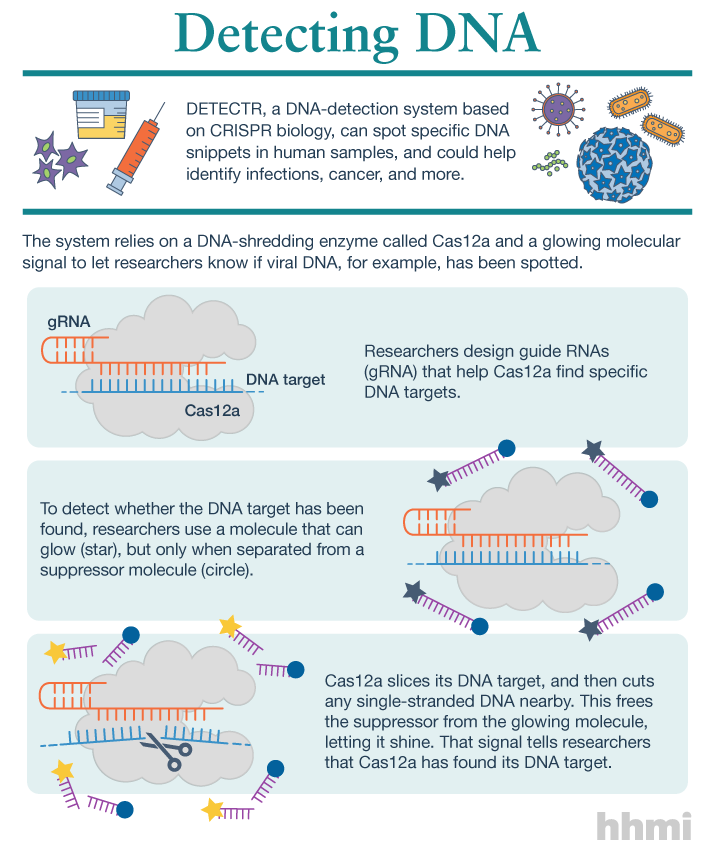

According to Chinese medical documents posted online this month (here and here), a team at the Southern University of Science and Technology, in Shenzhen, has been recruiting couples in an effort to create the first gene-edited babies. They planned to eliminate a gene called CCR5 in hopes of rendering the offspring resistant to HIV, smallpox, and cholera.

The clinical trial documents describe a study in which CRISPR is employed to modify human embryos before they are transferred into women’s uteruses.

The scientist behind the effort, He Jiankui, did not reply to a list of questions about whether the undertaking had produced a live birth. Reached by telephone, he declined to comment.

However, data submitted as part of the trial listing shows that genetic tests have been carried out on fetuses as late as 24 weeks, or six months. It’s not known if those pregnancies were terminated, carried to term, or are ongoing.

…

Apparently He changed his mind because Marilynn Marchione in a November 26, 2018 article for the Associated Press confirms the news,

A Chinese researcher claims that he helped make the world’s first genetically edited babies — twin girls born this month whose DNA he said he altered with a powerful new tool capable of rewriting the very blueprint of life.

If true, it would be a profound leap of science and ethics.

A U.S. scientist [Dr. Michael Deem] said he took part in the work in China, but this kind of gene editing is banned in the United States because the DNA changes can pass to future generations and it risks harming other genes.

Many mainstream scientists think it’s too unsafe to try, and some denounced the Chinese report as human experimentation.

…

There is no independent confirmation of He’s claim, and it has not been published in a journal, where it would be vetted by other experts. He revealed it Monday [November 26, 2018] in Hong Kong to one of the organizers of an international conference on gene editing that is set to begin Tuesday [November 27, 2018], and earlier in exclusive interviews with The Associated Press.

“I feel a strong responsibility that it’s not just to make a first, but also make it an example,” He told the AP. “Society will decide what to do next” in terms of allowing or forbidding such science.

Some scientists were astounded to hear of the claim and strongly condemned it.

It’s “unconscionable … an experiment on human beings that is not morally or ethically defensible,” said Dr. Kiran Musunuru, a University of Pennsylvania gene editing expert and editor of a genetics journal.

“This is far too premature,” said Dr. Eric Topol, who heads the Scripps Research Translational Institute in California. “We’re dealing with the operating instructions of a human being. It’s a big deal.”

However, one famed geneticist, Harvard University’s George Church, defended attempting gene editing for HIV, which he called “a major and growing public health threat.”

“I think this is justifiable,” Church said of that goal.

…

h/t Cale Guthrie Weissman’s Nov. 26, 2018 article for Fast Company.

Diving into more detail

Ed Yong in a November 26, 2018 article for The Atlantic provides more details about the claims (Note: Links have been removed),

… “Two beautiful little Chinese girls, Lulu and Nana, came crying into the world as healthy as any other babies a few weeks ago,” He said in the first of five videos, posted yesterday {Nov. 25, 2018] to YouTube [link provided at the end of this section of the post]. “The girls are home now with their mom, Grace, and dad, Mark.” The claim has yet to be formally verified, but if true, it represents a landmark in the continuing ethical and scientific debate around gene editing.

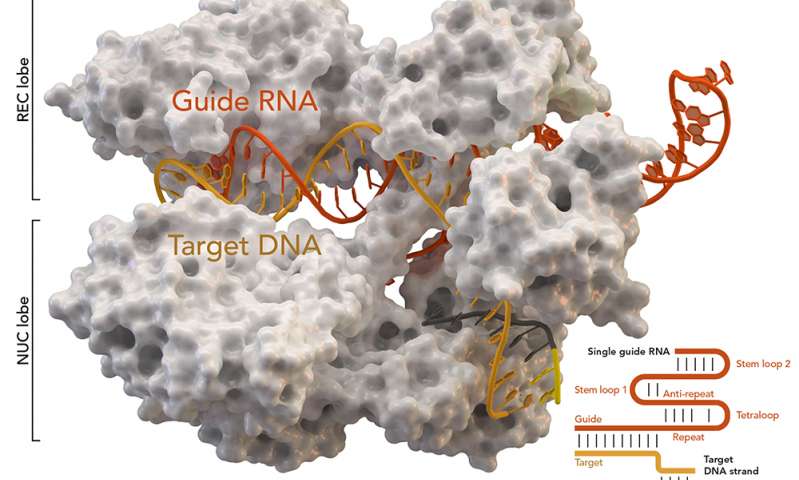

Late last year, He reportedly enrolled seven couples in a clinical trial, and used their eggs and sperm to create embryos through in vitro fertilization. His team then used CRISPR to deactivate a single gene called CCR5 in the embryos, six of which they then implanted into mothers. CCR5 is a protein that the HIV virus uses to gain entry into human cells; by deactivating it, the team could theoretically reduce the risk of infection. Indeed, the fathers in all eight couples were HIV-positive.

Whether the experiment was successful or not, it’s intensely controversial. Scientists have already begun using CRISPR and other gene-editing technologies to alter human cells, in attempts to treat cancers, genetic disorders, and more. But in these cases, the affected cells stay within a person’s body. Editing an embryo [it’s often called, germline editing] is very different: It changes every cell in the body of the resulting person, including the sperm or eggs that would pass those changes to future generations. Such work is banned in many European countries, and prohibited in the United States. “I understand my work will be controversial, but I believe families need this technology and I’m willing to take the criticism for them,” He said.

…

“Was this a reasonable thing to do? I would say emphatically no,” says Paula Cannon of the University of Southern California. She and others have worked on gene editing, and particularly on trials that knock out CCR5 as a way to treat HIV. But those were attempts to treat people who were definitively sick and had run out of other options. That wasn’t the case with Nana and Lulu.

“The idea that being born HIV-susceptible, which is what the vast majority of humans are, is somehow a disease state that requires the extraordinary intervention of gene editing blows my mind,” says Cannon. “I feel like he’s appropriating this potentially valuable therapy as a shortcut to doing something in the sphere of gene editing. He’s either very naive or very cynical.”

“I want someone to make sure that it has happened,” says Hank Greely, an ethicist at Stanford University. If it hasn’t, that “would be a pretty bald-faced fraud,” but such deceptions have happened in the past. “If it is true, I’m disappointed. It’s reckless on safety grounds, and imprudent and stupid on social grounds.” He notes that a landmark summit in 2015 (which included Chinese researchers) and a subsequent major report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine both argued that “public participation should precede any heritable germ-line editing.” That is: Society needs to work out how it feels about making gene-edited babies before any babies are edited. Absent that consensus, He’s work is “waving a red flag in front of a bull,” says Greely. “It provokes not just the regular bio-Luddites, but also reasonable people who just wanted to talk it out.”

…

Societally, the creation of CRISPR-edited babies is a binary moment—a Rubicon that has been crossed. But scientifically, the devil is in the details, and most of those are still unknown.

CRISPR is still inefficient. [emphasis mine] The Chinese teams who first used it to edit human embryos only did so successfully in a small proportion of cases, and even then, they found worrying levels of “off-target mutations,” where they had erroneously cut parts of the genome outside their targeted gene. He, in his video, claimed that his team had thoroughly sequenced Nana and Lulu’s genomes and found no changes in genes other than CCR5.

That claim is impossible to verify in the absence of a peer-reviewed paper, or even published data of any kind. “The paper is where we see whether the CCR5 gene was properly edited, what effect it had at the cellular level, and whether [there were] any off-target effects,” said Eric Topol of the Scripps Research Institute. “It’s not just ‘it worked’ as a binary declaration.”

…

In the video, He said that using CRISPR for human enhancement, such as enhancing IQ or selecting eye color, “should be banned.” Speaking about Nana and Lulu’s parents, he said that they “don’t want a designer baby, just a child who won’t suffer from a disease that medicine can now prevent.”

But his rationale is questionable. Huang [Junjiu Huang of Sun Yat-sen University ], the first Chinese researcher to use CRISPR on human embryos, targeted the faulty gene behind an inherited disease called beta thalassemia. Mitalipov, likewise, tried to edit a gene called MYBPC3, whose faulty versions cause another inherited disease called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Such uses are still controversial, but they rank among the more acceptable applications for embryonic gene editing as ways of treating inherited disorders for which treatments are either difficult or nonexistent.

In contrast, He’s team disableda normal gene in an attempt to reduce the risk of a disease that neither child had—and one that can be controlled. There are already ways of preventing fathers from passing HIV to their children. There are antiviral drugs that prevent infections. There’s safe-sex education. “This is not a plague for which we have no tools,” says Cannon.

As Marilynn Marchione of the AP reports, early tests suggest that He’s editing was incomplete [emphasis mine], and at least one of the twins is a mosaic, where some cells have silenced copies of CCR5 and others do not. If that’s true, it’s unlikely that they would be significantly protected from HIV. And in any case, deactivating CCR5 doesn’t confer complete immunity, because some HIV strains can still enter cells via a different protein called CXCR4.

Nana and Lulu might have other vulnerabilities. …

It is also unclear if the participants in He’s trial were fully aware of what they were signing up for. [emphasis mine] The team’s informed-consent document describes their work as an “AIDS vaccine development project,” and while it describes CRISPR gene editing, it does so in heavily technical language. It doesn’t mention any of the risks of disabling CCR5, and while it does note the possibility of off-target effects, it also says that the “project team is not responsible for the risk.”

He owns two genetics companies, and his collaborator, Michael Deem of Rice University, [emphasis mine] holds a small stake in, and sits on the advisory board of, both of them. The AP’s Marchione reports, “Both men are physics experts with no experience running human clinical trials.” [emphasis mine]

…

Yong’s article is well worth reading in its entirety. As for YouTube, here’s The He Lab’s webpage with relevant videos.

Reactions

Gina Kolata, Sui-Lee Wee, and Pam Belluck writing in a Nov. 26, 2018 article for the New York Times chronicle some of the response to He’s announcement,

It is highly unusual for a scientist to announce a groundbreaking development without at least providing data that academic peers can review. Dr. He said he had gotten permission to do the work from the ethics board of the hospital Shenzhen Harmonicare, but the hospital, in interviews with Chinese media, denied being involved. Cheng Zhen, the general manager of Shenzhen Harmonicare, has asked the police to investigate what they suspect are “fraudulent ethical review materials,” according to the Beijing News.

The university that Dr. He is attached to, the Southern University of Science and Technology, said Dr. He has been on no-pay leave since February and that the school of biology believed that his project “is a serious violation of academic ethics and academic norms,” according to the state-run Beijing News.

In a statement late on Monday, China’s national health commission said it has asked the health commission in southern Guangdong province to investigate Mr. He’s claims.

…

“I think that’s completely insane,” said Shoukhrat Mitalipov, director of the Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy at Oregon Health and Science University. Dr. Mitalipov broke new ground last year by using gene editing to successfully remove a dangerous mutation from human embryos in a laboratory dish. [I wrote a three-part series about CRISPR, which included what was then the latest US news, Mitalipov’s announcement, along with a roundup of previous work in China. Links are at the end of this section.’

Dr. Mitalipov said that unlike his own work, which focuses on editing out mutations that cause serious diseases that cannot be prevented any other way, Dr. He did not do anything medically necessary. There are other ways to prevent H.I.V. infection in newborns.

Just three months ago, at a conference in late August on genome engineering at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, Dr. He presented work on editing the CCR₅ gene in the embryos of nine couples.

At the conference, whose organizers included Jennifer Doudna, one of the inventors of Crispr technology, Dr. He gave a careful talk about something that fellow attendees considered squarely within the realm of ethically approved research. But he did not mention that some of those embryos had been implanted in a woman and could result in genetically engineered babies.

“What we now know is that as he was talking, there was a woman in China carrying twins,” said Fyodor Urnov, deputy director of the Altius Institute for Biomedical Sciences and a visiting researcher at the Innovative Genomics Institute at the University of California. “He had the opportunity to say ‘Oh and by the way, I’m just going to come out and say it, people, there’s a woman carrying twins.’”

“I would never play poker against Dr. He,” Dr. Urnov quipped.

Richard Hynes, a cancer researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who co-led an advisory group on human gene editing for the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine, said that group and a similar organization in Britain had determined that if human genes were to be edited, the procedure should only be done to address “serious unmet needs in medical treatment, it had to be well monitored, it had to be well followed up, full consent has to be in place.”

It is not clear why altering genes to make people resistant to H.I.V. is “a serious unmet need.” Men with H.I.V. do not infect embryos. …

Dr. He got his Ph.D., from Rice University, in physics and his postdoctoral training, at Stanford, was with Stephen Quake, a professor of bioengineering and applied physics who works on sequencing DNA, not editing it.

Experts said that using Crispr would actually be quite easy for someone like Dr. He.

After coming to Shenzhen in 2012, Dr. He, at age 28, established a DNA sequencing company, Direct Genomics, and listed Dr. Quake on its advisory board. But, in a telephone interview on Monday, Dr. Quake said he was never associated with the company.

Deem, the US scientist who worked in China with He is currently being investigated (from a Nov. 26, 2018 article by Andrew Joseph in STAT),

Rice University said Monday that it had opened a “full investigation” into the involvement of one of its faculty members in a study that purportedly resulted in the creation of the world’s first babies born with edited DNA.

Michael Deem, a bioengineering professor at Rice, told the Associated Press in a story published Sunday that he helped work on the research in China.

…

Deem told the AP that he was in China when participants in the study consented to join the research. Deem also said that he had “a small stake” in and is on the scientific advisory boards of He’s two companies.

…

Megan Molteni in a Nov. 27, 2018 article for Wired admits she and her colleagues at the magazine may have dismissed CRISPR concerns about designer babies prematurely while shedding more light on this latest development (Note: Links have been removed),

We said “don’t freak out,” when scientists first used Crispr to edit DNA in non-viable human embryos. When they tried it in embryos that could theoretically produce babies, we said “don’t panic.” Many years and years of boring bench science remain before anyone could even think about putting it near a woman’s uterus. Well, we might have been wrong. Permission to push the panic button granted.

Late Sunday night, a Chinese researcher stunned the world by claiming to have created the first human babies, a set of twins, with Crispr-edited DNA….

…

What’s perhaps most strange is not that He ignored global recommendations on conducting responsible Crispr research in humans. He also ignored his own advice to the world—guidelines that were published within hours of his transgression becoming public.

On Monday, He and his colleagues at Southern University of Science and Technology, in Shenzhen, published a set of draft ethical principles “to frame, guide, and restrict clinical applications that communities around the world can share and localize based on religious beliefs, culture, and public-health challenges.” Those principles included transparency and only performing the procedure when the risks are outweighed by serious medical need.

The piece appeared in the The Crispr Journal, a young publication dedicated to Crispr research, commentary, and debate. Rodolphe Barrangou, the journal’s editor in chief, where the peer-reviewed perspective appeared, says that the article was one of two that it had published recently addressing the ethical concerns of human germline editing, the other by a bioethicist at the University of North Carolina. Both papers’ authors had requested that their writing come out ahead of a major gene editing summit taking place this week in Hong Kong. When half-rumors of He’s covert work reached Barrangou over the weekend, his team discussed pulling the paper, but ultimately decided that there was nothing too solid to discredit it, based on the information available at the time.

Now Barrangou and his team are rethinking that decision. For one thing, He did not disclose any conflicts of interest, which is standard practice among respectable journals. It’s since become clear that not only is He at the helm of several genetics companies in China, He was actively pursuing controversial human research long before writing up a scientific and moral code to guide it.“We’re currently assessing whether the omission was a matter of ill-management or ill-intent,” says Barrangou, who added that the journal is now conducting an audit to see if a retraction might be warranted. …

…

“There are all sorts of questions these issues raise, but the most fundamental is the risk-benefit ratio for the babies who are going to be born,” says Hank Greely, an ethicist at Stanford University. “And the risk-benefit ratio on this stinks. Any institutional review board that approved it should be disbanded if not jailed.”

Reporting by Stat indicates that He may have just gotten in over his head and tried to cram a self-guided ethics education into a few short months. The young scientist—records indicate He is just 34—has a background in biophysics, with stints studying in the US at Rice University and in bioengineer Stephen Quake’s lab at Stanford. His resume doesn’t read like someone steeped deeply in the nuances and ethics of human research. Barrangou says that came across in the many rounds of edits He’s framework went through.

…

… China’s central government in Beijing has yet to come down one way or another. Condemnation would make He a rogue and a scientific outcast. Anything else opens the door for a Crispr IVF cottage industry to emerge in China and potentially elsewhere. “It’s hard to imagine this was the only group in the world doing this,” says Paul Knoepfler, a stem cell researcher at UC Davis who wrote a book on the future of designer babies called GMO Sapiens. “Some might say this broke the ice. Will others forge ahead and go public with their results or stop what they’re doing and see how this plays out?”

…

Here’s some of the very latest information with the researcher attempting to explain himself.

What does He have to say?

After He’s appearance at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing today, Nov. 27, 2018, David Cyranoski produced this article for Nature,

He Jiankui, the Chinese scientist who claims to have helped produce the first people born with edited genomes — twin girls — appeared today at a gene-editing summit in Hong Kong to explain his experiment. He gave his talk amid threats of legal action and mounting questions, from the scientific community and beyond, about the ethics of his work and the way in which he released the results.

He had never before presented his work publicly outside of a handful of videos he posted on YouTube. Scientists welcomed the fact that he appeared at all — but his talk left many hungry for more answers, and still not completely certain that He has achieved what he claims.

“There’s no reason not to believe him,” says Robin Lovell-Badge, a developmental biologist at the Francis Crick Institute in London. “I’m just not completely convinced.”

…

Lovell-Badge, like others at the conference, says that an independent body should confirm the test results by performing an in-depth comparison of the parents’ and childrens’ genes.

Many scientists faulted He for a lack of transparency and the seemingly cavalier nature in which he embarked on such a landmark, and potentially risky, project.

“I’m happy he came but I was really horrified and stunned when he described the process he used,” says Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley and a pioneer of the CRISPR/Cas-9 gene-editing technique that He used. “It was so inappropriate on so many levels.”

…

He seemed shaky approaching the stage and nervous during the talk. “I think he was scared,” says Matthew Porteus, who researches genome-editing at Stanford University in California and co-hosted a question-and-answer session with He after his presentation. Porteus attributes this either to the legal pressures that He faces or the mounting criticism from the scientists and media he was about to address.

…

He’s talk leaves a host of other questions unanswered, including whether the prospective parents were properly informed of the risks; why He selected CCR5 when there are other, proven ways to prevent HIV; why he chose to do the experiment with couples in which the fathers have HIV, rather than mothers who have a higher chance of passing the virus on to their children; and whether the risks of knocking out CCR5 — a gene normally present in people, which could have necessary but still unknown functions — outweighed the benefits in this case.

In the discussion following He’s talk, one scientist asked why He proceeded with the experiments despite the clear consensus among scientists worldwide that such research shouldn’t be done. He didn’t answer the question.

…

He’s attempts to justify his actions mainly fell flat. In response to questions about why the science community had not been informed of the experiments before the first women were impregnated, he cited presentations that he gave last year at meetings at the University of California, Berkeley, and at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. But Doudna, who organized the Berkeley meeting, says He did not present anything that showed he was ready to experiment in people. She called his defence “disingenuous at best”.

He also said he discussed the human experiment with unnamed scientists in the United States. But Porteus says that’s not enough for such an extraordinary experiment: “You need feedback not from your two closest friends but from the whole community.” …

…

Pressure was mounting on He ahead of the presentation. On 27 November, the Chinese national health commission ordered the Guangdong health commission, in the province where He’s university is located, to investigate.

On the same day, the Chinese Academy of Sciences issued a statement condemning his work, and the Genetics Society of China and the Chinese Society for Stem Cell Research jointly issued a statement saying the experiment “violates internationally accepted ethical principles regulating human experimentation and human rights law”.

The hospital cited in China’s clinical-trial registry as the that gave ethical approval for He’s work posted a press release on 27 November saying it did not give any approval. It questioned the signatures on the approval form and said that the hospital’s medical-ethics committee never held a meeting related to He’s research. The hospital, which itself is under investigation by the Shenzhen health authorities following He’s revelations, wrote: “The Company does not condone the means of the Claimed Project, and has reservations as to the accuracy, reliability and truthfulness of its contents and results.”

He has not yet responded to requests for comment on these statements and investigations, nor on why the hospital was listed in the registry and the claim of apparent forged signatures.

…

Alice Park’s Nov. 26, 2018 article for Time magazine includes an embedded video of He’s Nov. 27, 2018 presentation at the summit meeting.

What about the politics?

Mara Hvistendahl’s Nov. 27, 2018 article about this research for Slate.com poses some geopolitical questions (Note: Links have been removed),

…

The informed consent agreement for He Jiankui’s experiment describes it as an “AIDS vaccine development project” and used highly technical language to describe the procedure that patients would undergo. If the reality for some Chinese patients is that such agreements are glossed over, densely written, or never read, the reality for some researchers working in the country is that the appeal of cutting-edge trials is too great to resist. It is not just Chinese scientists who can be blinded by the lure of quick breakthroughs. Several of the most notable breaches of informed consent on the mainland have involved Western researchers or co-authors. … When people say that the usual rules don’t apply in China, they are really referring to authoritarian science, not some alternative communitarian ethics.

For the many scientists in China who adhere to recognized international standards, the incident comes as a disgrace. He Jiankui now faces an ethics investigation from provincial health authorities, and his institution, Southern University of Science and Technology, was quick to issue a statement noting that He was on unpaid leave. …

It would seem that US [and from elsewhere]* scientists wanting to avoid pesky ethics requirements in the US have found that going to China could be the answer to their problems. I gather it’s not just big business that prefers deregulated environments.

Guillaume Levrier’s (he’ studying for a PhD at the Universté Sorbonne Paris Cité) November 16, 2018 essay for The Conversation sheds some light on political will and its impact on science (Note: Links have been removed),

… China has entered a “genome editing” race among great scientific nations and its progress didn’t come out of nowhere. China has invested heavily in the natural-sciences sector over the past 20 years. The Ninth Five-Year Plan (1996-2001) mentioned the crucial importance of biotechnologies. The current Thirteenth Five-Year Plan is even more explicit. It contains a section dedicated to “developing efficient and advanced biotechnologies” and lists key sectors such as “genome-editing technologies” intended to “put China at the bleeding edge of biotechnology innovation and become the leader in the international competition in this sector”.

Chinese embryo research is regulated by a legal framework, the “technical norms on human-assisted reproductive technologies”, published by the Science and Health Ministries. The guidelines theoretically forbid using sperm or eggs whose genome have been manipulated for procreative purposes. However, it’s hard to know how much value is actually placed on this rule in practice, especially in China’s intricate institutional and political context.

In theory, three major actors have authority on biomedical research in China: the Science and Technology Ministry, the Health Ministry, and the Chinese Food and Drug Administration. In reality, other agents also play a significant role. Local governments interpret and enforce the ministries’ “recommendations”, and their own interpretations can lead to significant variations in what researchers can and cannot do on the ground. The Chinese National Academy of Medicine is also a powerful institution that has its own network of hospitals, universities and laboratories.

Another prime actor is involved: the health section of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which has its own biomedical faculties, hospitals and research labs. The PLA makes its own interpretations of the recommendations and has proven its ability to work with the private sector on gene editing projects. …

One other thing from Levrier’s essay,

… And the media timing is just a bit too perfect, …

Do read the essay; there’s a twist at the end.

Final thoughts and some links

If I read this material rightly, there are suspicions there may be more of this work being done in China and elsewhere. In short, we likely don’t have the whole story.

As for the ethical issues, this is a discussion among experts only, so far. The great unwashed (thee and me) are being left at the wayside. Sure, we’ll be invited to public consultations, one day, after the big decisions have been made.

Anyone who’s read up on the history of science will tell you this kind of breach is very common at the beginning. Richard Holmes’ 2008 book, ‘The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science’ recounts stories of early scientists (European science) who did crazy things. Some died, some shortened their life spans; and, some irreversibly damaged their health. They also experimented on other people. Informed consent had not yet been dreamed up.

In fact, I remember reading somewhere that the largest human clinical trial in history was held in Canada. The small pox vaccine was highly contested in the US but the Canadian government thought it was a good idea so they offered US scientists the option of coming here to vaccinate Canadian babies. This was in the 1950s and the vaccine seems to have been administered almost universally. That was a lot of Canadian babies. Thankfully, it seems to have worked out but it does seem mind-boggling today.

For all the indignation and shock we’re seeing, this is not the first time nor will it be the last time someone steps over a line in order to conduct scientific research. And, that is the eternal problem.

Meanwhile I think some of the real action regarding CRISPR and germline editing is taking place in the field (pun!) of agriculture:

My Nov. 27, 2018 posting titled: ‘Designer groundcherries by CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)‘ and a more disturbing Nov. 27, 2018 post titled: ‘Agriculture and gene editing … shades of the AquAdvantage salmon‘. That second posting features a company which is trying to sell its gene-editing services to farmers who would like cows that never grow horns and pigs that never reach puberty.

Then there’s this ,

‘The Genetic Revolution‘, a documentary that offers relatively up-to-date information about gene editing, which was broadcast on Nov. 11, 2018 as part of The Nature of Things series on CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation).

My July 17, 2018 posting about research suggesting that scientists hadn’t done enough research on possible effects of CRISPR editing titled: ‘The CRISPR ((clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)-CAS9 gene-editing technique may cause new genetic damage kerfuffle’.

My 2017 three-part series on CRISPR and germline editing:

CRISPR and editing the germline in the US (part 1 of 3): In the beginning

CRISPR and editing the germline in the US (part 2 of 3): ‘designer babies’?

CRISPR and editing the germline in the US (part 3 of 3): public discussions and pop culture

There you have it.

Added on November 30, 2018: David Cyanowski has written one final article (Nov. 30, 2018 for Nature) about He and the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing. He did not make his second scheduled appearance at the summit, returning to China before the summit concluded. He was rebuked in a statement produced by the Summit’s organizing committee at the end of the three-day meeting. The situation with regard to his professional status in China is ambiguous. Cyanowski ends his piece with the information that the third summit will take place in London (likely in the UK) in 2021. I encourage you to read Cyanowski’s Nov. 30, 2018 article in its entirety; it’s not long.

Added on Dec. 3, 2018: The story continues. Ed Yong has written a summary of the issues to date in a Dec. 3, 2018 article for The Atlantic (even if you know the story ift’s eyeopening to see all the parts put together.

J. Benjamin Hurlbut, Associate Professor of Life Sciences at Arizona State University (ASU) and Jason Scott Robert, Director of the Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics at Arizona State University have written a provocative (and true) Dec. 3, 2018 essay titled, CRISPR babies raise an uncomfortable reality – abiding by scientific standards doesn’t guarantee ethical research, for The Conversation. h/t phys.org

*[and from elsewhere] added January 17, 2019.

Added on January 23, 2019: He has been fired by his university (Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen) as announced on January 21, 2019. David Cyranoski provides a details accounting in his January 22, 2019 article for Nature.